How a discussion on Twitter has helped to identify the well-known malaria drug hydroxychloroquine as a possible treatment for Covid-19

What started as a Google doc shared on a niche Twitter thread has led to an open-data repository of clinical trials to test if hydroxychloroquine is an effective treatment for coronavirus.

At times like these, we are reminded of how fake news can spread rapidly on social media. That doesn’t mean, though, that the medium should just be discounted as an effective tool to share ideas and disseminate important information.

For example, a coronavirus discussion that started on the sidelines of Bitcoin Twitter—a place where I increasingly find myself spending too much of my spare time—has helped seed work to confirm whether a well-known malaria drug is an effective treatment for Covid-19.

It all started about two weeks ago, when an M.D. turned blockchain investor named James Todaro tweeted that a malaria drug called chloroquine was a potential treatment and preventative against the new coronavirus. Todaro linked to a Google doc he’d cowritten, explaining the idea, following a hat tip from an American expat, now living in China, named Adrian Bye.

Note that the Google doc has since been removed, however, it is available on GitHub here. Also note that, as reported by Wired, Johns Hopkins and Thomas Broker did not directly contribute to the paper and have been removed as coauthors per their request.

Chloroquine is nothing new; its use dates back to World War II, and it’s derived from the bark of the chinchona tree, like quinine, a centuries-old antimalarial. In fact, physicians understand it well and regularly prescribe it for a number of ailments, not just malaria.

There has been evidence that chloroquine is effective against viruses related to the new coronavirus, such as the one that causes SARS, for some time. It works by inhibiting a process called glycosylation, a chemical transformation of the proteins in the virus’s outer shell that’s part of the infection process. However, since February, reports out of China have suggested that chloroquine is also an effective treatment for Covid-19.

Following this, at a World Health Organisation (WHO) press conference, a reporter from the fact-checking group Africa Check asked whether chloroquine was an option. Janet Diaz, head of clinical care for the WHO Emergencies Program, said: “We recommend that therapeutics be tested under ethically approved clinical trials to show efficacy and safety.”

With that in mind, a French infectious disease researcher named Didier Raoult published a quick review of existing in vitro studies of chloroquine and the less toxic derivative hydroxychloroquine. He recommended not only to spin up research in humans but also to start using the drugs clinically.

Additional in vitro studies such as this one published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases on March 9, show that hydroxychloroquine is more effective than chloroquine against Covid-19.

So, back to Todaro’s tweet—it got thousands of likes. The engineer/tech world picked up the idea. Todaro’s coauthor, a lawyer named Gregory Rigano, even went on Fox News to talk about the concept. Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk tweeted about it, citing an explanatory YouTube video from a physician who’s been doing a series of coronavirus explainers.

Since then, Raoult has had promising results from a clinical trial of 20 patients and an observational study of 80 patients with Covid-19 treated with a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. He found that “hydroxychloroquine treatment is significantly associated with viral load reduction/disappearance in Covid-19 patients and its effect is reinforced by azithromycin.”

In the video below, Raoult discusses the results, highlighting the importance of treating people with moderate or severe infections at an early enough stage to avoid progression of pneumonia (at which point treatment with antivirals is less effective). Turn on English subtitles if you don’t speak French.

Then, three days ago (March 26), Raoult’s work was noted by Philippe Douste-Blazy, the former French Minister of Health who sits on the IHU Méditerranée Infection Board of Directors with Raoult.

It seems like Douste-Blazy’s influence has helped bring this research to the attention of the French government, which (also on March 26) announced that physicians in France may prescribe hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19.

Across the pond, in the US, the use of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for Covid-19 has also been gaining traction, with the President mentioning it in a White House briefing last week. However, as reported by CNN, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is not currently sponsoring any clinical trials for it, even though it’s pouring money into other coronavirus drug research (notably remdesivir and sarimulab).

As the CNN article suggests, this may be because pharmaceutical companies have exclusive rights to these drugs and have an incentive to get studies moving. Hydroxychloroquine, on the other hand, is an inexpensive generic drug made by several companies, so no one company stands to make much money off it.

“There are financial drivers in this system,” said Dr. Kevin Tracey, president of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell. “I think that’s just the reality, frankly.”

Here in the UK, the government seems to be taking a similar stance, waiting for the results of further clinical trials before licensing the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for Covid-19.

With that in mind, Todaro and Rigano are working with Raoult to speed this process up and are spinning up an open-data repository of clinical trials. They’re hoping to have clinicians enroll as subjects, and they’d then prescribe hydroxychloroquine to themselves as they treat patients with Covid-19. Case-matched physicians who didn’t want to take the drug, could then act as the control group.

“You can use historical controls, the rate of medical doctors being infected that were not on hydroxychloroquine regularly. And if there are doctors that would like to participate in the study that would like to not take hydroxychloroquine, they would also be excellent controls,” Rigano says. “Ethically speaking, we don’t want anyone to contract this virus. It’s really a wonderful design.”

Rigano and Todaro say there’s no time to waste, that the pandemic is moving too fast for traditional science. “That would take months,” Todaro says. “I’d hate to bank on things we would find in months, or a vaccine that comes out in mid to late 2021.”

So, while a Google doc shared over Twitter isn’t the typical way science gets done, it definitely seems to have had a big impact in this case and the tech world is paying attention.

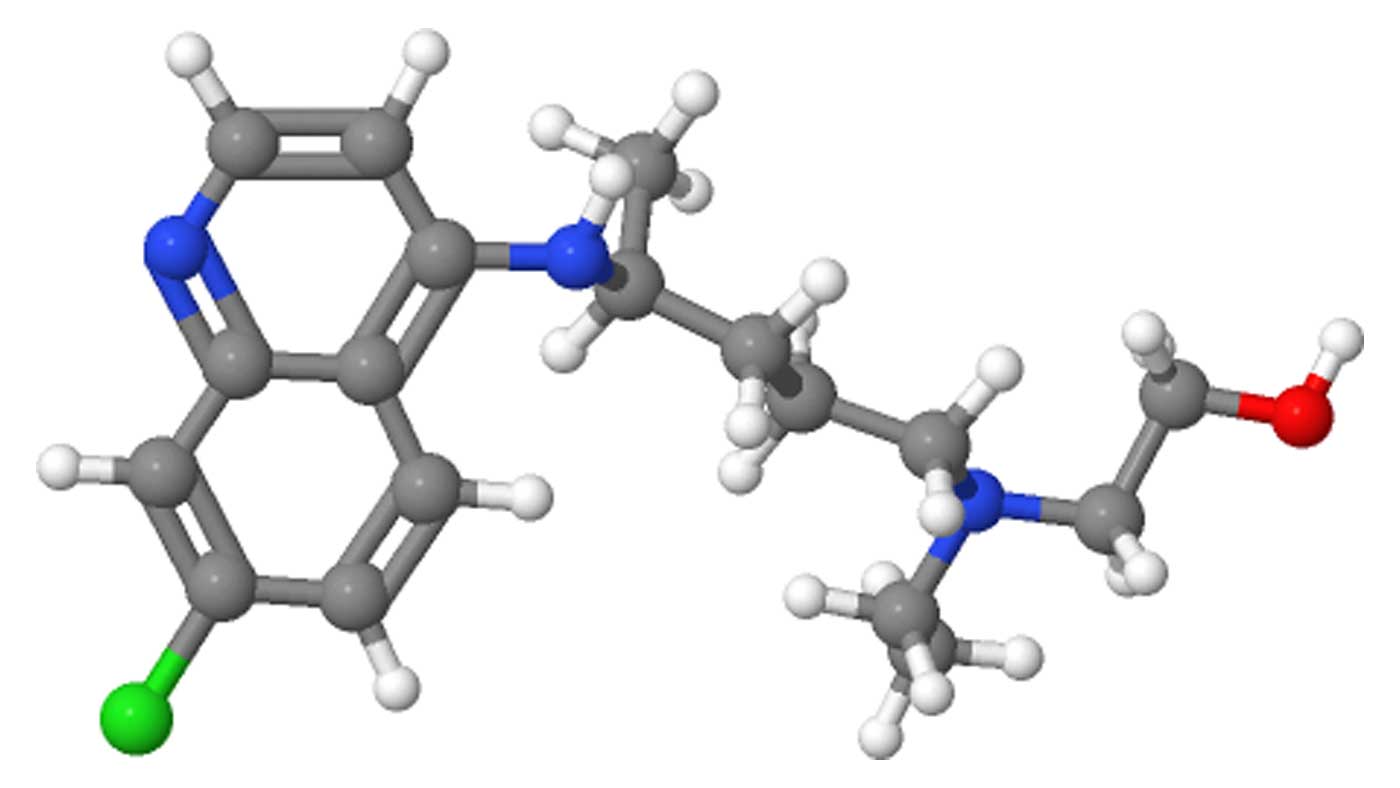

Featured image: 3D model of hydroxychloroquine molecular. Source: Chiral Jon/Flickr

This post is also available on our website at: adaptnetwork.com/science/how-discussion-on-twitter-has-helped-identify-malaria-drug-hydroxychloroquine-as-treatment-for-covid-19

Website: adaptnetwork.com

Hive: hive.blog/@adaptnetwork

Facebook: facebook.com/adaptnetwork

Twitter: twitter.com/adaptnet

Minds: minds.com/adaptnetwork

Shared on Twitter here as part of @ocd's #posh (Proof Of SHare) initiative

This post is also available on our website at: adaptnetwork.com/science/how-discussion-on-twitter-has-helped-identify-malaria-drug-hydroxychloroquine-as-treatment-for-covid-19