Is any of the Lost Abenmoad story true? How wrong is the unaware consensus view?

Does a 600-year-old copy of a 1000-year-old Arabic manuscript, formerly held by the king of Libya, threaten a covert NATO monopoly on quick digital decryption?

Chapter 1 of Zigzag Sphere — a serial inquiry

Words Copyright © 2018 by Mark Lane Vines. A Busy.org / Steemit.com online exclusive. Images from CC0 Wikimedia sources, except for photos of Austin’s old East-West Center, provided by friends of the author who got married there.

about the author

§

FOR FIFTY-ODD YEARS, covert NATO agencies have known how to factorize very large composite numbers and perform related computations — thereby penetrating public key encryption — rapidly and with ease. Unless you use one-time-pad technology, your digital message traffic is open to NATO surveillance. Higher math enables their cyberspies to pry. Yet their monopoly on this math is fragile and precarious. Once, in 1983–84, it was (almost?) broken. Diagrams from an (almost?) unknown medieval treatise by ibn Muadh al-Jayyani, viewed by someone with relevant expertise, reportedly did the trick, and could suffice to do so again. Libya is the document’s last known location. In 2005, a filmmaker whose father had seen it was abducted and abusively interrogated by rogue Pakistani Army officers who sought its secrets. In 2011, civilians were killed in a NATO bombing of a private home suspected of storing it. Ever since Gaddhafi fell, rival powers have been racing to retrieve it.

Many news reports look different in this light, notably the 2013 exposure of emails from the account of Sidney Blumenthal by Romanian hacker Marcel-Lehel Lazar, the original Guccifer.

True, false, or somewhere in between, that in brief is the story thus far of the Lost Abenmoad. In 1984, part of the story was broadcast throughout the USA on National Public Radio. A few cypherpunks, Arabists, and conspiracy buffs have tracked the story since then. Yet, aside from scarce comments of my own, it has never been mentioned online in English anywhere. For a controversial and fascinating story formerly given radio airtime nationwide, this is a peculiar outcome. I’ve tried to interest others in researching and telling the story, to no avail. I guess, at least for now, I’m the only one willing to mention it again. And that is what makes this a Busy / Steemit exclusive.

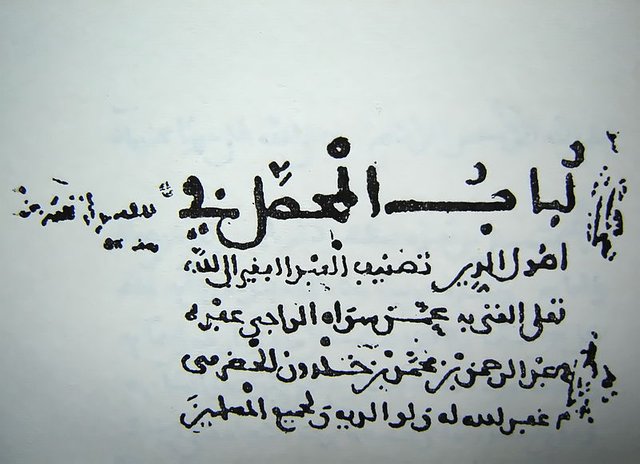

The photo above shows the handwriting of ibn Khaldun, the very man who commissioned the scribal effort at al-Qarauwiyn that produced copies of the Lost Abenmoad, as part of an anthology of works on spherical calculation, most from the period now known as the Golden Age of Islam. Each copy of this anthology, including one reportedly entrusted to the Senussi, was graced by a calligraphic title page in the same handwriting.

IN EARLY 1984, at age 23, I was between two failed attempts to earn a university degree, living with my parents again, and working for an overnight photo developing firm. Having written for school newspapers in high school and college, I was still considered a likely journalist by several of my friends. Let me call one of them “Nottingham Law” — not his actual name — or Ham for short. One day Ham rang me up on the telephone.

An announcer at a public radio station, Ham advised me that an interesting segment would soon be broadcast on “All Things Considered,” the weekday evening news and variety program, then produced by National Public Radio (now by NPR.org). Ham and other station personnel had heard the segment already. Knowing my fascinations well, he assured me, “It’ll be right up your alley. Don’t miss it!”

As it happened, I tuned in late, and so I did miss part of it. However, Ham and I and interested mutual friends discussed the segment extensively over the next few days, “filling me in on” the info I had not heard for myself.

The segment was an interview with a game theorist from the UK who believed his life was in danger from covert NATO agencies and figured a dose of publicity could change that. He used his real name then, but it might be unwise to repeat it now, so let me call him “Benedict Benedict” instead — or, to avoid its peculiar doubling effect, “Ben Benedict” for short. The story he told was a strange one. Though skepticism was the first and strongest response my friends and I felt, we also quoted Mark Twain to each other: “Interesting if true — and interesting anyway.”

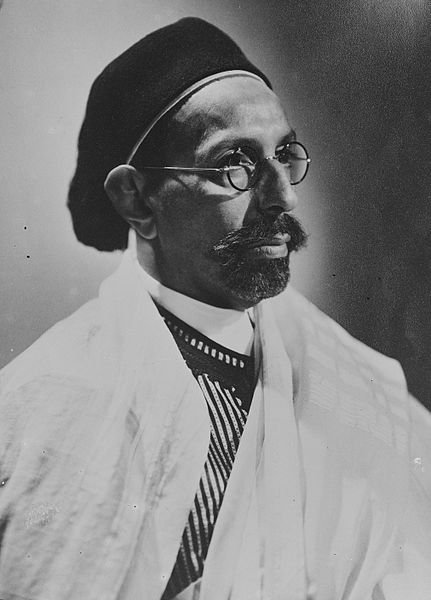

Idris, first and only king of Libya, in 1951, shortly before Libya’s formal independence was declared. Image from the Dutch Nationaal Archief and Spaamestad Photo, by Fotograaf Onbekend / Anefo.

Did this ruler honor his country’s brightest pupils with lessons that he himself taught?

THE PREVIOUS MAY, when the former king of Libya died in exile, Benedict — by his own report — was living next door to a man who, in his youth, had met the king. Benedict described his neighbor as a developmental psychologist whose father, a travel writer, Arab yet not Libyan, had been a friend of the king.

Benedict invited his neighbor in, to express what the passing away of the former king meant to him. Let me call the neighbor “Lubayd al-Wali as-Satna” and the neighbor’s father “jad Tahir as-Satna” — though these are not their actual names. As Lubayd reminisced about his encounter with the king, the impact on Benedict was extraordinary.

According to Lubayd, the king made it his practice to honor Libya’s best students with “royal lessons” in which Idris himself taught them some aspect of their heritage. (I have not been able to verify that such lessons really occurred or that they were taught by the king.) Somehow, jad Tahir arranged for Lubayd — in spite of their status as foreigners — to attend a session of this type at a palace in Benghazi.

The lesson, as Lubayd recalled it, concerned spherical trigonometry. Because of cultural factors like geometric pattern art and religious obligations to face Mecca at prayer and in burial, spherics was long an Islamic specialty. Indeed the first treatise on spherical trig was The Book on Unknown Arcs of a Sphere by a Muslim, the Andalusian Arab geometer ibn Muadh al-Jayyani, whose name was Latinized by European scholars in several different ways, among them “Abenmoad.”

During this particular lesson, Lubayd said, the king made use of the Spherics Collection, a centuries-old anthology of documents on spherics-related calculations, not only displaying them to the students, but also reading aloud from them and even sketching some of their diagrams on a chalkboard. (I have not been able to obtain a physical description of this document collection, except that its title calligraphy was done by ibn Khaldun.) According to Benedict, Lubayd was clearly delighted by the king’s erudition and proud of his father for having such a friend.

In the process, the king exposed his pupils not only to the well-attested pioneering work just mentioned, The Book on Unknown Arcs of a Sphere, but also to what the king called “the second book of the al-Jayyani pair,” a sequel that — according to Lubayd — concerned regular polyhedra in spherical projection. A mathematician himself, Benedict had a chalkboard in his home. With Benedict’s encouragement, Lubayd used it to sketch several diagrams from his memory of the “royal lesson” that the king had given some 30 years before.

Benedict was conscious of his neighbor’s grief at the former king’s passing. For Lubayd, the “royal lesson” represented a bygone era of promise, and he was also grieving for its brevity and failure. Yet Benedict himself grew increasingly elated as the narrative continued.

Benedict felt sure that the sequel, “the second book of the al-Jayyani pair,” had to be a rarity, virtually unknown in the developed world. (I have not been able to verify that the sequel really ever existed. Surveys of al-Jayyani’s life and works do not mention any treatise on spherical polyhedra. A reported attestation by Abu al-Hakam al-Kirmani seems as elusive as the Lost Abenmoad itself.) Lubayd confirmed this impression by saying that other copies of the sequel, and the original at al-Qarauwiyn, all appeared to have been lost; Lubayd said the Senussi copy was the only one still extant, even though Ahmad ibn Idris (1760–1837) gave at least three copies of the Spherics Collection to great teachers of the ijtihad reasoning tradition that he had revived.

In the context of modern mathematical advances — a context unknown to Lubayd, yet well known to Benedict — the ideas he was hearing, and the diagrams on his chalkboard, amounted to a thunderbolt Eureka revelation.

Benedict Benedict believed he was now mentally solving one of the toughest remaining problems in the whole history of mathematics: how to categorize, and rapidly factorize, very large composite numbers.

Above, Gaussian primes near the origin of the complex plane. Image by User:Hack, using Mathematica 6.0.

BENEDICT PROMPTLY ASSEMBLED — again, by his own report — a small team of mathematicians to test the conjecture that had taken shape in his mind while his neighbor Lubayd reminisced about the lesson King Idris taught. There were some initial difficulties. Apparently the number of categories, into which very large composite numbers naturally fall, was larger than they first thought. Within a few months, however, all of their tests were successful, and the rest of the team began to share Benedict’s elation and excitement. Although no rigorous proof had been developed, and none might be for generations, they agreed the time to announce the conjecture had come. Slowly, with exquisite care, they began to prepare a journal article for peer review and publication.

Then, as Benedict was packing for a long-planned visit to the USA, he lost contact with two members of his team. The rest of them assured Benedict that, while he was in America, they would track down the two who had seemingly disappeared. He boarded the plane.

At his hotel, the day after his arrival, Benedict was accosted by men claiming to represent a covert American agency that he did not name. They told him his missing teammates were safe, and would remain unharmed if he “played ball” with their agency. However, they told him sternly, his conjecture on rapid factorization of very large composite numbers must never see the light of day. He would never experience the fame he thought himself and his team were due for solving that problem. His conjecture had to remain secret, at the highest conceivable classification, throughout and beyond the foreseeable future.

Anyway, they told him, he was not the first. The same conjecture had been secretly developed by NATO mathematicians decades earlier, years before the first crude Soviet prototype of a digital encryption system. All such systems have been vulnerable to NATO penetration ever since. If the conjecture were ever published, it would enable the Soviet Union and other powers to penetrate digital security as easily as NATO could.

Benedict understood this to be a slight exaggeration. Digital encryption based on the one-time-pad method would still be secure. Yet the agents confronting Benedict felt sure that public key encryption would be far more widely employed, because it conveniently allows the use of insecure channels for key exchange.

They told him — in early 1984! — they expected a digitally networked future in which military and government affairs, intelligence and counter-intelligence, banking, and corporate security in every nation would all rely on forms of crypto dependent on the apparent inability of computers to solve certain math puzzles quickly. Their own hardware and software, however, incorporating covert mathematical advances like Benedict’s own conjecture, would give them a window into all such secret affairs, everywhere, around the world.

§

It would greatly endanger this NATO advantage, they warned Benedict, if his conjecture became public, exposing all the same secrets to surveillance by the Soviets and other such rival powers. The agents reminded him of many atrocities committed by totalitarian dictatorships that were actively seeking to undermine or defeat the West. Himself an anti-communist, Benedict sympathized.

They told him he was doomed by his conjecture to face a terrible choice: recruitment, or worse. Recruitment — working for one of the agencies that already possessed the knowledge his team had begun to gain — would be fairly lucrative, but it would also mean steeping himself in a guarded life of in-group isolation and secrecy, shorn of the free sociability and the easy ideational interchange that had characterized the best of his career. What they meant by worse they did not specify.

Once they had given him a deadline for decision and left, Benedict immediately conceived of a third option. He already had tenure (or its Welsh equivalent). Without much risking his quality of life or his rate of pay, without betraying his nation or its allies to their Cold War enemies, without enhancing the surveillance capabilities of totalitarian tyrants, he could insure himself against covert official threats to his life and freedom by making himself a laughingstock in his chosen profession.

This would be easy. Boastful claims for his conjecture, presenting it as “an historic achievement” without ever describing it or providing evidence for it, would suffice. All he needed was a public venue.

And so Benedict Benedict strode straight into the studios of National Public Radio, told journalists there that he had solved the biggest problem in mathematics, refrained from supporting this claim with a description or evidence, reprimanded NATO agents “on the air” for their threats and coercion, and warned them that — because of the new publicity that his radio interview was earning — his disappearance, imprisonment, or death would inflame public interest and expose the very secret that NATO wanted to conceal.

“My safety and health are now vital, instead of problematic, to the West. So long as I remain a crackpot, living and at liberty,” he declaimed, “no one will bother to believe how deeply and how broadly into all manner of human affairs the highest echelons of history’s greatest alliance now can pry. To put them on notice of my new standing is why I came forward today. Let us hope no more need be said of it henceforth.”

Above, Egypt’s president Gamal Abdel Nasser, left, receiving Libya’s leader Muammar Gaddhafi, far right, along with “a member of the Libyan Revolutionary Command Council,” after the 1969 overthrow of Libya’s monarchy. Image by Al-Ahram Weekly.

Could the person standing between and behind Nasser and Gaddhafi in the photo be RCC member Khweldi Hamedi — also styled Khweldi el Hameidi or Khuwaildi al-Humaidi — the Libyan Army major who arrested Crown Prince Hasan el Senussi during the coup?

UPON HEARING THIS radio program — except for its beginning, which I missed — and after discussing it with some interested friends, I persuaded Nottingham Law to obtain Ben Benedict’s mailing address from National Public Radio, and sent Benedict a polite letter filled with technical questions. Benedict responded with even greater courtesy, but few satisfactory answers, except for an assurance that his formerly missing teammates were fine. Though I intended to keep our correspondence, and indeed kept it for 13 years, it seems to have gone missing in 1997, during the move to my current house. In recounting this story here, I have likely made errors that stem from this loss.

Benedict did commit to the future publication of hints to the factorization method implied by his conjecture, should the Cold War ever abate. He later kept his word, publishing two books that included not only hints, but even diagrams. (They showed a polyhedron, yet not in spherical projection.) No Eureka revelations resulted. In a later chapter, perhaps I will discuss Benedict’s books further.

By a convenient coincidence, as Ham had realized before he rang me on the phone, I already knew more about Benedict’s neighbor Lubayd than Benedict had mentioned in the radio broadcast. Identified by Benedict as a developmental psychologist, Lubayd was also author of several books on Eastern wisdom traditions, and headed a society devoted to the same topic. An avid reader and collector, I owned some of his books, in which the society’s address could be found.

Of course, I also addressed polite questions to Lubayd, care of the society he led. He never answered. However, members of that society began to make sporadic appearances in my life, asking me questions and volunteering scraps of information, often at times when I was not free to steer the interaction — for instance, visiting me at work while I was busy, or at school while I was hastening to class. Only one of them ever gave me his full name, phone number, or any way to contact him. In several cases, I could not figure out how they had even found me in the places where their paths intersected with mine.

The first phase of these contacts lasted from 1984 to 1992. Most of them were one-on-one encounters. On a single more dramatic occasion, society members conducted a well-attended chanting meditation at the now-defunct East-West Center, a “New Age” chapel, event venue, and vegeterian restaurant, formerly of Austin, Texas. The society planned the event so as to raise funds for Afghan resistance against Soviet occupation. This too I will discuss briefly below, and more in a later chapter.

Bit by bit, as if on a film negative spooling its way through a developer, a picture of the Lost Abenmoad emerged from the scraps they fed me. To my consternation, this included no physical descriptions of the manuscript or the Spherics Collection that contained it. Paper in a binder? Parchments in scrolls? All black ink? Ink of additional colors? Any signs of damage? I cannot say, because they never said. The emerging picture did include some info on the conceptual contents of these documents. It included more on the story of their provenance. Later chapters will address these matters as well.

Another important aspect of the emerging picture was what might have happened to the Lost Abenmoad after Libya’s monarchy fell.

Besides being king, long before he became king, Idris was the chief of a mystical-chivalric fraternal Islamic missionary order that had been led by a succession of his ancestors and played a huge role in the history of Libya, especially its eastern region, Cyrenaica. This order had the same name as his family — Senussi — also styled Sanusi or Sanusiyah. Chiefs of the order were always heads of the family, but the rest of the order’s leadership and its membership could come from any family that welcomed the order to their town.

The order had its own ethos, its own mystique. Its members were taught many skills, including military disciplines, used for instance in rebellion against Italian colonial occupation. The order built and staffed mosques, fraternal lodges, and schools across northern Africa and the Sudan. The Senussi copy of the Spherics Collection, including the Lost Abenmoad, belonged as much to the Senussi order as to the Senussi clan. For a time, the collection was kept at a Senussi fraternal lodge in Tuniyn, an outlying village of the fabled locale Ghadames in Tripolitania, Libya’s western region, close to its border with Tunisia. Later it was kept, and shown to students, in the prestigious and influential Senussi University, at Jaghbub in Cyrenaica.

(Although some commentaries date the Senussi University in Jaghbub to 1953, it was already old then. Its campus was visited in the 1920s by Ahmed Bey Hassanein, who took photos of people and the mosque there, and published an account of his visit, now maintained online by SaharaSafaris.org. Moreover, in a biography of Omar al-Mukhtar, also styled Umar Mukhtar, Abdul Latip Talib states that Mukhtar studied at the same campus while in his teens, which would have been between 1875 and 1881.)

King Idris was both out of Libya for medical treatment, and preparing to abdicate in favor of the crown prince, when the Senussi monarchy was overthrown. Aligned with Nasser in Egypt, this coup by the RCC met with popular enthusiasm and astonishingly little violence as it took control of the country. Yet its leadership knew that, if serious opposition took shape, its nuclei would likely be local chapters of the Senussi order.

Slowly and steadily, therefore, the legislative bodies of Libya under Gaddhafi declared that more and more properties of the Senussi clan and the Senussi order must be forfeited to the state. This process picked up speed after the king’s death. Under the monarchy, the line between family, order, and state had been blurry anyway. Also, Senussi clan members had been accused of embezzling public properties. Thus the state’s claim to some of these properties enjoyed a measure of legitimacy. And, with each new legislative declaration of forfeiture, it was often Khweldi Hameidi who led the forces that seized the forfeited properties.

According to my sources, the property seizures were sometimes marred by theft, assault, and fire. From 1984 onward, various relatives of the former king were evicted from their homes and made to watch them burn. The Senussi University in Jaghbub was reduced to rubble by 1988 if not before.

Did Khweldi Hamedi and the forces he led try to obtain the Lost Abenmoad, with or without the rest of the Spherics Collection, on behalf of the Libyan state? Was the document damaged or destroyed? Was Hamedi successful in obtaining it? If so, was it brought to Gaddhafi? Stored in a state facility? Did it stay with Hamedi for safekeeping?

Too secretive to tell me their full names or give me their contact info, the society members whom I met nevertheless insisted they were unafraid of the NATO agencies that had so frightened Benedict. More than unafraid, they said they were working with those agencies to recover the missing al-Jayyani sequel. This collaborative goal did not, however, seem to strike them as especially urgent. Even if Gaddhafi or Hamedi were to gain — or already had — possession of the Lost Abenmoad, they said, its value would remain completely unsuspected by leaders of the Gaddhafi regime.

This assurance and lack of urgency would eventually prove the opposite of prophetic.

Meanwhile, except for the fact that I had written their leader, I could not make out why they were telling me any of this. And why were these “covert NATO agencies” leaving me unmolested as I spent years pursuing their most highly classified secret?

Then, in 1992, I learned that jad Tahir as-Satna and Lubayd al-Wali as-Satna had been accused in the 1970s of hyping, and planning to forge, a fictitious Persian manuscript, allegedly some eight centuries old. Their accuser, a crusty Celt with diplomatic experience, ridiculed their failure to produce the manuscript, and sarcastically offered to find them a capable forger. Yet no manuscript emerged, the hype faded, and the accusation fizzled out.

§

Upon learning this, however, I began drawing ugly conclusions about my sources in the traditional wisdom society Lubayd led. Already, the only source whose name I knew had fallen out with me, because we had quarreled over claims that “colored rains” in Afghanistan were due to “mycotoxin” weapons allegedly used against the Afghan people by their Soviet occupiers. Now, mewly mistrusting the as-Satna father and son, I started to impugn the motives of the sources connected with them.

Also in 1992, the sporadic visits from sources came to a halt. At first I foolishly wondered if they were psychically aware of having lost my confidence. Later, I realized that the 1992 death of Libya’s crown prince might have terminated some ambition of theirs that they had been intriguing to achieve only while he was alive.

The Lost Abenmoad was an invented myth, I decided, and my sources, at Lubayd’s instigation, intended for me to hype its legend. Eventually, I reasoned, the society Lubayd led would fabricate a fake manuscript and sell it off to some gullible collector who believed the story. Disgusted at my own gullibility, though I had never fully believed the story, I swore off any further pursuit of the topic, even destroying all my notes. I would not regret this till 2005.

§

Errors in this recounting of the Lost Abenmoad story have likely resulted from the destruction of my notes.

Above, a woodcut illustration of the fable recorded by Aesop, “The Farmer and his Sons,” from a German translation by Heinrich Steinhöwel.

THIS ENGLISH VERSE from The Herford Aesop by Oliver Herford (1863–1935) nicely tells the tale:

“An aged Farmer, fearing lest

His land, when he was laid to rest,

Might lie untilled, before he died

Summoned his sons to his bedside

And told them that a Treasure rare

Was buried in a field somewhere.

No sooner was he laid away

Than setting to, without delay

His sons plowed up each field with care,

To find at last the Treasure rare

Was not a chest with guineas filled

But rich crops from the land they tilled.”

Copying a manuscript by hand is tedious work. The scribal effort at al-Qarauwiyn, initiated by ibn Khaldun, that collected various works on spherical calculation into a single anthology was much more difficult than simple straightforward copying. The authors to be anthologized had used incompatible forms of numeric notation, which had not as yet been standardized in their distant era. A few of these authors, according to my sources, feared that negative numbers might be perceived as impious or even as evil, and employed peculiar notation strategies to prevent any need for their use. Other authors willingly used negative numbers, but used notation forms that differed in other ways.

Ibn Khaldun insisted that the copyists transform all works in the anthology, diagrams included, redesigning them so that students and other users of the Spherics Collection would not need to learn more than one system for notating numbers and calculations.

Motivating copyists to perform such detailed labor with high accuracy was a challenge. From what my sources told me, since before ibn Khaldun was born, a favorite trick of scriptorium headmasters was to create a legend, or start a rumor, convincing their copyists that the manuscripts to be reproduced might contain secrets of alchemy, such as chrysopoeia, how to transmute lead into gold, not in plain text, but in some symbolic code. When dealing with a mathematical manuscript — laborious even to follow, let alone copy, and never mind redesign — this kind of rumor greatly increased the document’s chances of successful propagation.

Of course, as these documents could not enable anyone to change a cheap metal into literal gold, to spread a rumor like that was to tell a lie. However, like the farmer’s tale of treasure in Aesop’s fable of the lazy sons, it was a lie intended to produce an instrumental effect in service of good. Such lies were told and retold in scholarly scriptoria without a qualm.

My sources, members of the society Lubayd led, believed that ibn Khaldun was gifted with foresight. Evidently, however, he did not foresee how long the legend of transmutation secrets would persist in its attachment to the treatise now known as the Lost Abenmoad. It lasted long enough to reach Muammar Gaddhafi, and he at least half believed it. Or so I was told in 2005, by which time Lubayd had already passed away.

Gaddhafi thought of transmuting one metal into another as a matter for nuclear science, and rightly so. But chrysopoeia by neutron bombardment is not practical, given current knowledge, as a cost-effective way to produce gold, partly because the atoms transmuted are only a small scattered percentage of the atoms in any sample being bombarded. Gaddhafi may have gotten wind of NATO’s interest in the Lost Abenmoad, and mistaken that for confirmation of its nuclear significance, concluding that it might make chrysopoeia practical.

§

Evidently he thought it possible that neutron bombardment in a cavity with a polyhedral shape, or a spherical cavity lined with materials in a spherical polyhedral pattern, would result in the transmutation of all atoms in a sample, instead of a random few. In this he was almost certainly wrong, and would have been frustrated by any experiments that he might have ordered.

So — and fatefully — Gaddhafi turned for help to his contacts in the nuclear proliferation network associated with A.Q. Khan that conveyed uranium enrichment technology to Iran and Libya and enabled Pakistan and North Korea to develop atomic bombs. The timing of this consultation is unknown, but could have been a delicate affair.

By March 2003, Gaddhafi was already beginning to help expose this very network to NATO and the IAEA as part of an effort by Libya to placate the West. Some nuclear scientists whom Gaddhafi consulted might have become estranged from him as their exposure became apparent.

Afterward, on separate occasions during 2005, several filmmakers and manuscript collectors in their travels through Pakistan were abducted and abusively interrogated by Pakistani Army officers whose actions were subsequently condemned and labeled “rogue” by the Pakistani government, military, and ISI. One of those mistreaded in this way was a son of Lubayd. Let me call him “Hafid Iqbal as-Satna” — not his actual name.

§

Twice before this, I had attempted to contact Hafid Iqbal with questions about the Lost Abenmoad. He never answered. (No member of the as-Satna family has ever spoken or corresponded with me.) Despite this rebuff, curiosity had led me to check the web regularly for updates on Hafid Iqbal’s career. When reports of his misadventure in Pakistan surfaced, I took notice, and paid close attention to his public statements on the matter.

Before 2005 ended, when visiting an Austin area used bookstore to sell some of my books, I encountered one of my old sources there, from the society formerly led by the late Lubayd. We recognized and greeted each other. Let me call him “Ikraam,” though it would surprise me if that were his actual name.

Ikraam struck up a fairly long comversation with me as I waited for the bookstore staff to price the books I’d brought and make me an offer. During our talk, Ikraam asked me if I were aware that Hafid Iqbal had been “tortured” earlier that year in Pakistan. I answered Yes and quoted a remark by Hafid Iqbal to the effect that his interrogation, while traumatic, seemed to serve no purpose.

Ikraam then contradicted that remark. He said one interrogator, a Pakistani Army captain, had shown Hafid Iqbal photocopied pages from the Lost Abenmoad and shouted questions at him about what his father Lubayd had revealed to him about alchemical nuclear secrets concealed in the text. Ikraam also said that Hafid Iqbal’s previous residence in Wales had involved the UK in getting him released from captivity. As a result, Hafid Iqbal had been debriefed by the British government. This meant NATO now knew Gaddhafi had shared the contents of the Lost Abenmoad with military scientists in A.Q. Khan’s network, and would never again be complacent about Gaddhafi’s access to the document.

Ikraam then predicted that NATO would therefore override Gaddhafi’s rapprochement with the West and take action to to overthrow “his” regime. Ikraam further predicted NATO would attack various buildings and properties belonging to Khweldi Hamedi, and anyplace else believed likely to hold the Lost Abenmoad copy that the Libyan state had presumably seized from the Senussi, in hopes that the document could be confiscated or destroyed.

Though history would later validate both predictions, I reacted at the time with (undue?) angry skepticism toward Ikraam and what he had just told me.

“I have read, heard, and watched every interview given and statement made by Hafid Iqbal on his abduction and interrogation,” I insisted, and rightly, so far as the English language was concerned. “Hafid Iqbal has nowhere mentioned the Lost Abenmoad in public or for publication at any time. I don’t know what gives you the idea that this document ever existed. I don’t know where you got the information that he was interrogated about its contents. Did one of his torturers perhaps tell you?”

Ikraam blinked, paused, and responded. “It is always good to ‘balance between doubt and belief,’” he quoted. “Yet I’m surprised you can doubt us that strongly after what you experienced at the East-West Center. What greater proof of our baraka transmission could you possibly want?”

§

I have given this response considerable thought.

Six years later, during Libya’s version of an Arab Spring uprising, NATO took advantage of UN authorization for civilian protection operations to carry out a bombing campaign, substituting denials for explanations. State storage facilities and civilian homes belonging to families allied with Gaddhafi, including Khweldi Hamedi’s family, were bombed. On the 19th of June 2011, NATO blamed a missile malfunction for having recently hit Hamedi’s office in Tripoli. On the 20th of June, eight bombs hit a Hamedi home in Sorman, killing 13. Indeed, the bombing campaign caused many civilian deaths. It also enabled rebels to achieve “regime change” — and capture and murder Gaddhafi.

Above, musicians of the Jay Williams Tribe, a band in performance at a November 1986 wedding. Behind them is the exterior of the East-West Center, formerly on South Fifth in Austin, Texas, but defunct since 1989, when the building was hauled away after being damaged by fire. Sometime within a year or so before this wedding, members of the society Lubayd led conducted a chanting meditation for the public inside this building.

I DIDN’T PAY close attention to the chanting meditation, or its introductory explanation. It was held in 1986 (or late 1985?) in the East-West Center, already a familiar setting for me, though I had been living in Austin then for less than two years. It was a demonstration of a spiritual practice known as the Dervish Call, convened as a fundraising event in support of Ahmad Shah Massoud and his Afghan mujahideen, resistance fighters against the Soviet occupation. It was reasonably well attended by a mostly male American mix, of what I took to be “New Age” wisdom seekers wearing jeans and T-shirts, and conservative anti-communists wearing suits.

Inside the doors, bananas and a water dispenser with cups were placed on a small table but, having just eaten, I did not imbibe. The Center was mostly one main room, which I considered a kind of chapel room. Like everyone else attending, I went straight in there. A group of mostly bearded men in mostly foreign garb were sitting on the floor in a corner, around a young American man in a pressed shite shirt and light brown slacks, who stood up, signaled for quiet, and welcomed us. He told us to sit on the floor too. The floor had a black-and-white checkerboard or chessboard pattern, a signature feature of the East-West Center interior space.

The young American emcee, still standing, explained that we would be hearing the chant “Ya Hu,” intended as a remembrance of God invoking God’s names, especially a name referring to God as Friend. This got garbled in my inattentive mind. I thought the emcee was telling us that the word Hu means Friend, and continued to think so for years. Hu is actually an Arabic pronoun that generally means He.

After these remarks, the emcee identified a white-bearded man among the foreigners close to him as an Afghan spiritual master in charge of the demonstration. Slight scattered applause ensued, muted and curtailed, I thought, by the impression that the “master” hadn’t noticed he was being introduced. After inviting us to join the chant with our own voices, the emcee sat down, somebody started lightly patting a hand drum, and the chanting began.

All of the men sitting in the same corner as the emcee and the “master” chanted. Their voices were melodic in some exotic scale. Mostly they repeated the phrase “Ya Hu,” yet occasionally repeated other phrases too. Though I have never been competent in Arabic, I did study it briefly, and even I could recognize a few phrases as verses from the Quran.

Suddenly I was no longer there. Neither was the checkerboard floor, nor any other space, nor time. My body, my thoughts, my identity were gone. There was no chanting, no drumming, no touch, no hot or cold, no sensory impression of any kind except white light. A single unbounded point filled with effortless white light permeated everything forever.

§

I snapped out of it and looked around. The chanting had not stopped. The people in attendance mostly seemed like they were getting bored with it. And then, soon enough, it was over.

People stood up and milled around. The “master” and the bearded foreign chanters kept aloof. The emcee spent some time speaking with several people, including me. He requested that I try to raise money for the mujahideen, recommended several ways of doing so, and told me about one way the “master” could help. I politely declined, suggesting I might be able to raise funds in some other, less dramatic way.

Then the event was over. I left. I don’t remember telling anyone about my visionary “white light” experience for decades afterward. Certainly I never told Ikraam or anyone else in the society Lubayd led. So how did Ikraam know, in 2005, that I had experienced a “proof of baraka transmission” at the East-West Center nearly 20 years earlier?

Presumably Ikraam was present at the chanting meditation, perhaps as one of the people chanting. And perhaps my body or my posture gave some outward tell-tale sign that I was having an inner visionary experience, much as movements of the eyes behind the closed lids of a dreamer can show an outside observer when the dreaming stage of sleep is underway.

Or it could be that my “white light” experience was deliberately induced by a trick involving hypnosis, a drug, and/or audio effects. Others in attendance might also have been similarly affected. If so, Ikraam might have known what was done, and understood its likely impact on me. I discount the drug explanation to some extent because — if I recall correctly — I did not eat or drink anything while there.

Another possibility, of course, is that Ikraam learned of my inner experience by some psychic or paranormal connection. Or maybe he made a lucky guess.

It’s clear that, whether by trickery, art, science, or baraka, Dervish Call performers are seasoned practitioners of consciousness alteration. Yet my consciousness may have been less responsive than Ikraam expected. Rather than reverencing the baraka channel that it might have been taken to prove, I had basically just bracketed my “white light” experience as another unexplained weirdness in a weird life and shrugged it off.

§

By coincidence, the only putative contemporary reference to a second treatise on spherics by ibn Muadh al-Jayyani also reportedly alludes to a “names of God” chanting meditation technique, not the Dervish Call, but a different form of meditation. My sources attributed this reference to Abu al-Hakam al-Kirmani, whom they quoted as saying al-Jayyani, having mystically “heard the Name in his heartbeat and replaced his body with the Prophet’s own, was twice rewarded by God with splendid proofs.”

This apparently refers to a meditative technique associated, at least by scholars writing in English, with followers of Bahauddin Naqshband (1318–1389), and imputing knowledge of the same technique to Muslims in al-Andalus three centuries earlier might be anachronistic. Because the technique interferes with autonomic physiology, it could be dangerous if attempted without proper guidance.

In safely vague terms, the techique involves identifying subtle yet vital sounds and rhythms of the body with different Arabic names of God. The heartbeat, in particular, is identified with the name “Allah,” in accordance with one interpretation of surah 50:16, the “jugular vein” verse in the Qaf chapter of the Quran. The novitiate practices mentally chanting these names in outward silence until every systole-diastole cardiac cycle is heard as “Allah,” and the other sounds and rhythms are heard as the names assigned to them. After that, the novitiate reconceives his own body as having been mystically replaced by that of Muhammad. The resulting devotional state is a receptive one that God may reward with revelations of whatever is good for the novitiate to know.

In the case of ibn Muadh, “once” presumably means that the “splendid proofs” in his well-attested Book of the Unknown Arcs of a Sphere were a reward from God for his meditation, while “twice rewarded” presumably confirms the existence of a sequel to that book, endowed with “splendid proofs” not found in the first. (However, I have not yet been able to verify that Abu al-Hakam al-Kirmani actually made this remark. I don’t even have the Arabic original of the wording for which to search.) In any case, whether insights into the spherical projection of regular polyhedra are best achieved by devotional meditation, or by skeptical speculative calculation, remains an open question.

The last time I met Ikraam was in 2014, in another used bookstore belonging to the same chain. He mentioned the Blumenthal emails exposed by Guccifer as including a reference to $60,000 spent on a botched attempt to obtain the Lost Abenmoad in Tuniyn, an attempt Ikraam characterized in US government parlance as a Top Secret Special Access Program.

Above, another photo from the same wedding as the previous image, showing the chapel room with its checkerboard floor where, on a different occasion before either photo was taken, I attended a chanting meditation and experienced a mystical inner “white light” vision.

I DON’T KNOW how much, if any, of the unverified Lost Abenmoad story is true. I know only what happened to me — and, with my notes destroyed and my correspondence lost, even that much is a dubious matter of memory, research, and reconstruction.

I’m no longer so scandalized as I was in 1992 by the prospect that the story is a hoax. For one thing, Lubayd, the likely instigator, is dead. (Benedict could be dead also. If alive, he is extremely old.) For another, considered as a hoax, the story’s artistry now fascinates me. Perhaps, if not for some intervening factor, it would have culminated in the forging of a fake manuscript. Or perhaps a fake actually was forged. In either case, I would love to see the instructions given the forger!

Another possibility intrigues me: Even if the description Lubayd gave Benedict of the “royal lesson” featuring “the second book of the al-Jayyani pair,” sketches and all, was a liar’s invention, the conjecture it provoked in Benedict might still have been a genuine solution to the rapid prime factorization problem.

The prospect that the story is to some degree true still grips me. The National Public Radio broadcast that introduced me to the whole affair does not seem to be archived or mentioned online in English anywhere. The truer the story, the more officially secret it must be.

So why discuss it now?

Knowing a great secret estranges you from consensus thought emerging among people unaware of the secret. Even just wondering if you might know a great secret can estrange you from the unaware consensus view.

§

For instance, if NATO’s higher echelons have really been able to penetrate strong digital encryption with ease and speed for the last fifty-odd years, then the news reports of intelligence failures and security breaches — like the Iraqi WMD mistake, various emergent surveillance disclosures, and the OPM hack — are nothing but “limited hang-outs,” mere theater meant to induce underestimation of NATO’s actual surveillance capabilities. The unaware consensus view of these events would thus require significant reinterpretation.

I’d like to start feeling less lonely in thinking about this.

The development of distributed ledgers and cryptocurrencies makes assessment of their actual vulnerabilities critical for people who make and use them. While NATO may be unlikely to intervene in a manner that exposes any quick digital decryption monopoly they might have, the cryptocoin sector could still face a situation where new currencies need to be, not only “quantum resistant” in some hazy future after qubit ordinator technology becomes commercially viable, but also — and more urgently — “factorization resistant” right now.

§

So, after the pattern of the arms race and the space race, I hope the Lost Abenmoad story can trigger a kind of multilateral math race: a factorization race, a cryptography race, for the sake of secure decentralized digital currencies and the neo-prosperity they promise.

To make that race more multilateral, I seek help from anyone who can participate in translating this and other chapters of ZigZag Sphere, including technical jargon, accurately into such languages as Arabic, Urdu, Chinese, Russian, and Hindi.

I also seek help from anyone who feels qualified to investigate, or to declare, how true or false any aspect of the Lost Abenmoad story might be. In particular, any encounters with copies or photocopies of any medieval treatise on spherical polyhedra would be of interest, and likewise any evaluation of a factorization conjecture like the one that Benedict Benedict claimed.

This chapter has been a long one, I know, very long by Busy / Steemit norms. Many details have been omitted that would have made it even longer. And it focuses too much on me, when I am only tangential to the story. Yet I wanted a single posting that would cover something close to the story’s whole span, and I had no perspective to offer except my own. So I hope that this chapter can serve.

§

Questions, answers, criticisms, and suggestions are welcome in the comments.

more to come

Upvote • Follow • Resteem if you like!

Are you there?

Oh, I am indeed here, thank you!

I miss you too much dear

To the question in your title, my Magic 8-Ball says:

Hi! I'm a bot, and this answer was posted automatically. Check this post out for more information.

I have linked to this story on Facebook.

Here is the next installment, Chapter 2.