What exactly is the "biological clock" that has won a Nobel Prize in Medicine?

We all have an intuitive notion of what the biological clock is, that internal chronometer that adapts our physiology to the different phases of the day and causes us to experience disorders like jet lag when there is a temporary change in our environment. But how exactly does it work?

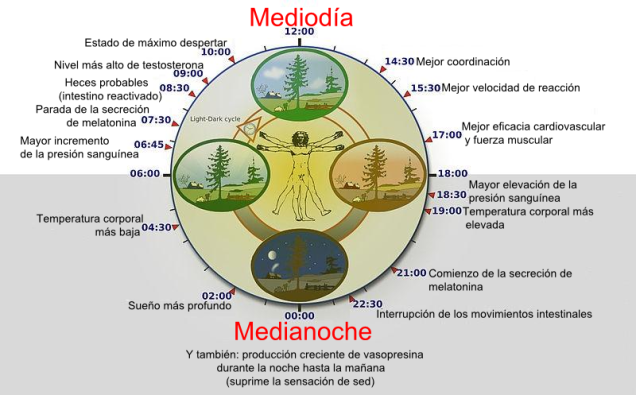

Although it sounds like popular wisdom, it is pure chemistry: there is indeed a "clock" in the body that precisely regulates functions such as behavior, hormone levels, sleep, body temperature and metabolism. There are also indications that a chronic mismatch between our lifestyle and the rhythm dictated by that biological clock carries a greater risk of suffering certain diseases. Scientists Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young, winners of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Medicine, elucidated over the years the inner workings of that system. This is what they discovered.

The circadian rhythms

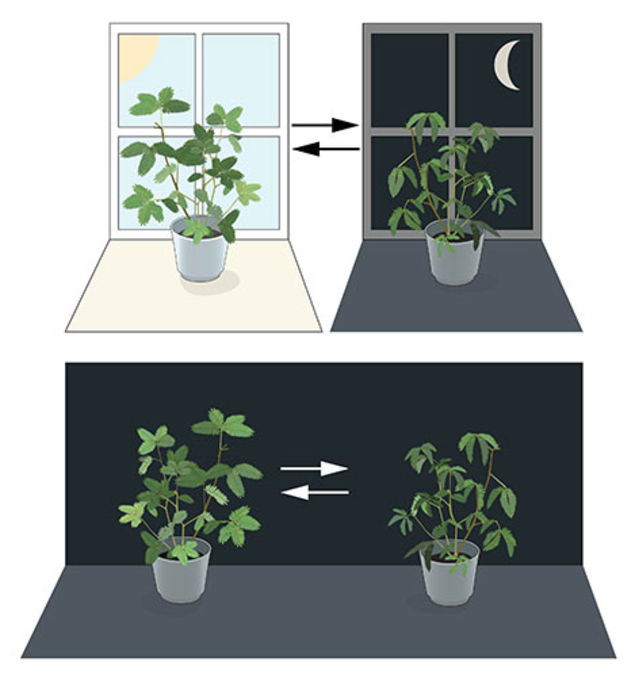

Life on Earth is adapted to the rotation of the planet. Plants, animals and humans are able to anticipate the day and night to adjust our biological rhythm accordingly. This is not new. In the eighteenth century, astronomer Jean Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan realized that certain plants opened their leaves during the day and closed them during the night. He wondered what would happen if the plant were placed in constant darkness and discovered that, regardless of sunlight, the leaves continued to open and closed every 24 hours. The plants seemed to have their own biological clock. We soon realized that these biological oscillations were a common feature of most living organisms, including animals.

We traveled until the 60s. At that time, the French explorer Michel Siffre spent long periods of time living underground, without clock or sunlight, in order to study their own biological rhythms. He once spent six months in a cave and his natural rhythm settled a little over 24 hours, though sometimes extended up to 48 hours. Also in the 1960s, investigators Jürgen Aschoff and Rütger Wever shoved a handful of people into a World War II bunker and found that most had a biological rhythm between 24 and 25 hours, although some stretched until 29 hours . It was at that time that the biologist Franz Halberg, the main driver of chronobiology, coined the term "circadian rhythms" from the terms circa ("around") and diem ("day").

The period gene

But what causes these circadian rhythms? In the 1970s, geneticist Seymour Benzer and his student Ronald Konopka wondered if it could be a gene, and worked with fruit flies to show that the mutations of a hypothetical gene named "period" could alter the circadian rhythms of these genes annoying insects. It was not until 1984 that Jeffrey Hall and Michael Rosbash of Brandeis University in Boston and Michael Young of Rockefeller University in New York succeeded in isolating the gene using fruit flies.

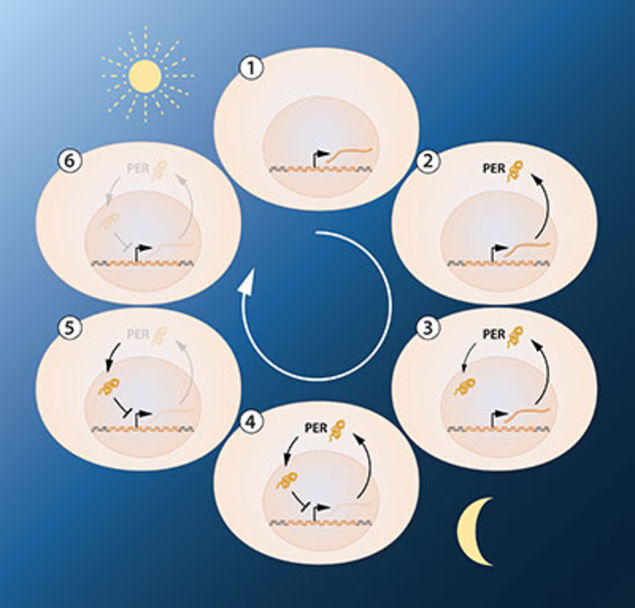

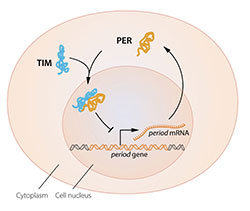

The researchers demonstrated that the gene period encodes a protein called PER whose levels oscillate in a 24-hour cycle in synchrony with the circadian rhythm. PER protein accumulates in the cell overnight and then degrades during the day. Nobel winners also identified other protein components that make up a precise clockwork mechanism within the cell that we know as the biological clock.

A mechanism that regulates itself

The next objective was to understand how the circadian oscillations of the biological clock were generated and maintained. Hall and Rosbash believed that the PER protein inhibited its own synthesis with a feedback loop that blocked the gene period, but for that it had to reach the cell nucleus, where the genetic material was. How did he get there?

In 1994, Michael Young discovered a second gene that encoded a protein called TIM and was responsible for circadian rhythms. In their study, Young demonstrated that when TIM bound to PER, the proteins were able to enter the nucleus of the cell to block the activity of the gene period and close the inhibitory feedback loop.

A new science

Today we know that a large part of our genes are regulated by that mechanism we call the biological clock. Many functions of physiology have been carefully calibrated at the cellular level by our circadian rhythm to adapt to the different phases of the day. We also know that these endogenous cycles establish a very stable relationship with the environmental cycles, and that is why they can fail if we spend several months buried in a cave.

Circadian biology has become a vast and dynamic field of research, with implications for our health and well-being. The biological clock even influences how we are affected and how the drugs move within the organism. Now we understand why flying east causes more jet lag than doing it westward, which is the best time to have a coffee or why sometimes it costs us to go to bed even though we have to get up early. Thanks to the work of Hall, Rosbash and Young, the human body has one less mystery.

Well researched write up.