First two major Asset Bubbles In History

The term "bubble", in reference to a financial crisis, finds its origins in the 1711–1720 British South Sea Bubble. At the beginning the term referred to the companies themselves, and their inflated stock, rather than to the crisis itself. Official notoriety for the term was gained with The Bubble Act 1720 (6 Geo I, c 18), which forbade the creation of joint-stock companies without royal charter, was promoted by the South Sea company itself before its collapse.

An asset bubble occurs when the price of a financial asset or commodity rises to levels that are well above either historical norms or its intrinsic value, or both. The problem is that since the intrinsic value of an asset can have a very wide range, a bubble is often justified by the flawed assumption that the asset's intrinsic value itself has skyrocketed or, in other words, the asset is fundamentally worth much more than it was in the past.

The Dutch Tulip Bubble

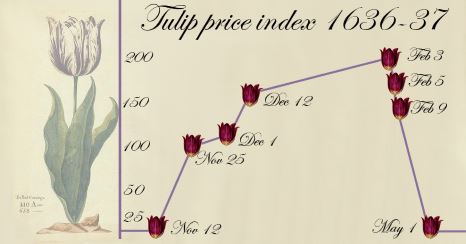

During the Dutch Golden Age contract prices for some bulbs of the recently introduced and fashionable tulip reached extraordinarily high levels and then dramatically collapsed in February 1637 thus generating Tulip mania (Dutch: tulpenmanie). This is generally considered the first recorded speculative bubble.

Formal futures markets appeared in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century. The most notable futures market revolved around the tulip market. In February 1637, a single tulip bulb sold for more than 10 times the annual income of a skilled worker.

Tulip mania reached its peak during the winter of 1636–37, when some bulbs were reportedly changing hands ten times in a day. No deliveries were ever made to fulfill any of these contracts, because in February 1637, tulip bulb contract prices collapsed abruptly and the trade of tulips ground to a halt.

The bubble probably burst in Haarlem, when, for the first time, buyers refused to show up at a bulb auction. Some historians assert this may have been because Haarlem was then in the wast in the midst of a of an outbreak of bubonic plague.

People were purchasing bulbs at higher and higher prices, intending to re-sell them for a profit. However, such a scheme could not last unless someone was ultimately willing to pay such high prices and take possession of the bulbs. In February 1637, tulip traders could no longer find new buyers willing to pay increasingly inflated prices for their bulbs. As this realization set in, the demand for tulips collapsed, and prices plummeted—the speculative bubble burst.

A relief came from t he self-regulating guild of Dutch florists which on February 24, 1637, in a decision that was later ratified by the Dutch Parliament, announced that all futures contracts written after November 30, 1636, and before the re-opening of the cash market in the early Spring, were to be interpreted as option contracts. They did this by simply relieving the futures buyers of the obligation to buy the future tulips, forcing them merely to compensate the sellers with a small fixed percentage of the contract price.

The Tulip mania had lasting effects on the Dutch but also influenced economics all over the world without necessarily being a lesson form which people learned something positive, mainly because of the easy money that speculation promises.

British South Sea Bubble

In 1711 „The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of fishing” was incorporated as a public-private partnership to consolidate and reduce the cost of national debt. The company was granted a monopoly to trade with South America, hence its name.

During the company's incorporation and subsequent existence Spain controlled South America and Britain was involved in the War of the Spanish Succession. These facts made no realistic prospect that trade would take place and the company would realize any significant profit from its monopoly.

The South Sea Bubble was created by a more complex set of circumstances than the Dutch Tulipmania, but has nevertheless gone down in history as another classic example of a financial bubble. Some of the more important causes of the bubble where: The Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 was not recognized immediately in the Spanish colonies thus the majority of slaves were eventually sold at a loss in the West Indies; When the government changed, so too did the company board and not always to the companies benefit; During the War of the Quadruple Alliance the company's assets in South America were seized; Trading more debt for equity;

The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumors" of the value of its potential trade in the New World; this was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy". The price of the stock went up over the course of a single year from about £100 to almost £1000 per share.

In early August 1720 the level of selling was such that the price started to fall, dropping back to £100 per share before the year was out, triggering bankruptcies among those who had bought on credit, and increasing selling, even short selling. Also, in August 1720, the first of the installment payments of the first and second money subscriptions on new issues of South Sea stock were due. As a result, many shareholders could not pay for their shares except by selling them.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Sea_Company