CANADIAN INDIAN FAMILIES WERE INDEMNIFIED BY THE SEPARATION OF THEIR CHILDREN.

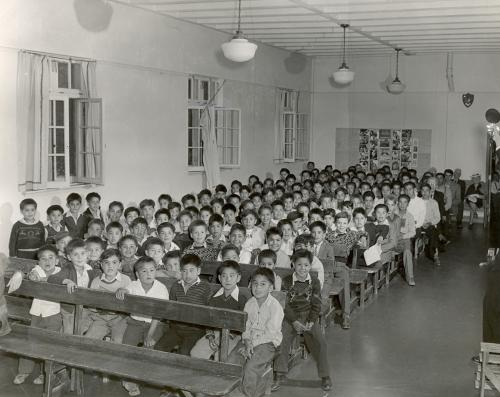

Children’s dining room, Indian Residential School, Edmonton, Alberta. Between 1925-1936. United Church Archives, Toronto, From Mission to Partnership Collection.

Image source

It is sad to know that the Catholic churches lend themselves to this abominable mistreatment of children, only to consider that they should be assimilated to be included in society.

But everything has an end and thank God this situation ended, but leaving great consequences in these children today adults.

Many of these children died in the boarding schools because of the mistreatment they had there.

At present, they are still paying compensation, which I consider not even paying all the money in the world could correct the years lived.

Here is the content and testimonies of the events that took place at that time.

The Canadian state is paying its historical debts with what they call "first nations." Ottawa has agreed to pay compensation to the thousands of indigenous children, now adults, who were forcibly separated from their communities and adopted by non-indigenous families.

These children were deprived of their cultural identity when social services dedicated to childhood separated them from their families during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Many of them consequently lost contact with their culture and language.

Some 20,000 people will receive state compensation, which will consist of a total amount of 750 million Canadian dollars (596 million US dollars) to be distributed among all beneficiaries.

The term residential schools refers to an extensive school system set up by the Canadian government and administered by churches that had the nominal objective of educating Aboriginal children but also the more damaging and equally explicit objectives of indoctrinating them into Euro-Canadian and Christian ways of living and assimilating them into mainstream Canadian society. The residential school system operated from the 1880s into the closing decades of the 20th century. The system forcibly separated children from their families for extended periods of time and forbade them to acknowledge their Aboriginal heritage and culture or to speak their own languages. Children were severely punished if these, among other, strict rules were broken. Former students of residential schools have spoken of horrendous abuse at the hands of residential school staff: physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological. Residential schools provided Aboriginal students with an inferior education, often only up to grade five, that focused on training students for manual labour in agriculture, light industry such as woodworking, and domestic work such as laundry work and sewing.

Residential schools systematically undermined Aboriginal culture across Canada and disrupted families for generations, severing the ties through which Aboriginal culture is taught and sustained, and contributing to a general loss of language and culture. Because they were removed from their families, many students grew up without experiencing a nurturing family life and without the knowledge and skills to raise their own families. The devastating effects of the residential schools are far-reaching and continue to have significant impact on Aboriginal communities. Because the government’s and the churches’ intent was to eradicate all aspects of Aboriginal culture in these young people and interrupt its transmission from one generation to the next, the residential school system is commonly considered a form of cultural genocide.

From the 1990s onward, the government and the churches involved—Anglican, Presbyterian, United, and Roman Catholic—began to acknowledge their responsibility for an education scheme that was specifically designed to “kill the Indian in the child.” On June 11, 2008, the Canadian government issued a formal apology in Parliament for the damage done by the residential school system. In spite of this and other apologies, however, the effects remain.

European settlers in Canada brought with them the assumption that their own civilization was the pinnacle of human achievement. They interpreted the socio-cultural differences between themselves and the Aboriginal peoples as proof that Canada’s first inhabitants were ignorant, savage, and—like children—in need of guidance. They felt the need to “civilize” the Aboriginal peoples. Education—a federal responsibility—became the primary means to this end.

The purpose of the residential schools was to eliminate all aspects of Aboriginal culture. Students had their hair cut short, they were dressed in uniforms, and their days were strictly regimented by timetables. Boys and girls were kept separate, and even siblings rarely interacted, further weakening family ties. In addition, students were strictly forbidden to speak their languages—even though many children knew no other—or to practise Aboriginal customs or traditions. Violations of these rules were severely punished.

Residential school students did not receive the same education as the general population in the public school system, and the schools were sorely underfunded. Teachings focused primarily on practical skills. Girls were primed for domestic service and taught to do laundry, sew, cook, and clean. Boys were taught carpentry, tinsmithing, and farming. Many students attended class part-time and worked for the school the rest of the time: girls did the housekeeping; boys, general maintenance and agriculture. This work, which was involuntary and unpaid, was presented as practical training for the students, but many of the residential schools could not run without it. With so little time spent in class, most students had only reached grade five by the time they were 18. At this point, students were sent away. Many were discouraged from pursuing further education.

Abuse at the schools was widespread: emotional and psychological abuse was constant, physical abuse was meted out as punishment, and sexual abuse was also common. Survivors recall being beaten and strapped; some students were shackled to their beds; some had needles shoved in their tongues for speaking their native languages. These abuses, along with overcrowding, poor sanitation, and severely inadequate food and health care, resulted in a shockingly high death toll. In 1907, government medical inspector P.H. Bryce reported that 24 percent of previously healthy Aboriginal children across Canada were dying in residential schools. This figure does not include children who died at home, where they were frequently sent when critically ill. Bryce reported that anywhere from 47 percent (on the Peigan Reserve in Alberta) to 75 percent (from File Hills Boarding School in Saskatchewan) of students discharged from residential schools died shortly after returning home.

In addition to unhealthy conditions and corporal punishment, children were frequently assaulted, raped, or threatened by staff or other students. During the 2005 sentencing of Arthur Plint, a dorm supervisor at the Port Alberni Indian Residential School convicted of 16 counts of indecent assault, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Douglas Hogarth called Plint a “sexual terrorist.” Hogarth stated, “As far as the victims were concerned, the Indian residential school system was nothing more than institutionalized pedophilia.

One of the main plaintiffs whose battle has ended in this arrangement, Marcia Brown Martel, who was separated from her family by social services and forcibly adopted by a non-indigenous family, called these cases "child robberies".

Brown Martel, who went through the reception service and suffered emotional, physical and sexual abuse, expressed hope that, after this victory, "this never happens again in Canada."

Cardinal was one of the thousands of children of the native tribes of Canada separated from their biological families between 1960 and the mid-1980s and sent with white families, who according to the authorities could then give them better care. Many of them lost contact with their culture and language.

It is a case similar to that of Canadian residential schools. Some 150,000 members of the original nations, the Inuit and the Metis were removed from their families for much of the last century and placed in government schools, where they were forced to convert to Christianity and were forbidden to speak their native language. Many were beaten and received insults, and it is said that up to 6,000 would have died.

The government of Canada apologized and paid compensation to the victims of this type of centers, and is now compensating those affected by what is known as "Sixties Scoop", when the children were removed from their reserves and indigenous families. But many say that the agreement is too low and too late.

COLLEEN CARDINAL

Cardinal says she will not erase what for her was a traumatic experience. She was separated from her family, in Alberta, and sent to a house about 1,600 miles away, by a lake in rural Ontario, where she and her two older sisters were sexually abused.

"We had to flee that house to escape physical and sexual violence, and my two older sisters were sexually assaulted," Cardinal said.

A few years earlier, Cardinal was surprised to discover that she was indigenous.

"When you are a child you want to hear that they love you and that people love you," he explained. "What I heard instead was 'Well, we chose you from a catalog of native children for adoption.'

The only catalog Cardinal knew was the Sears department store, not the government lists or religious organizations that included pictures of children available for adoption.

"I was thinking 'Is there a catalog of indigenous children like me?' That remained in my mind always happens, that I was selected from a catalog of indigenous children, "he said.

The victims of the "Sixties Scoop" began to sue the government of Canada in 2010, claiming damages for the loss of their language, culture and identity. Ontario Supreme Court Justice Edward Belobaba ruled last February 2017, that the country had breached its "duty of care" towards children and said the authorities were responsible.

The agreement, which is estimated to reach 20,000 people, seeks to resolve numerous related complaints. The victims will share $ 586 million dollars in individual compensation that will be determined later. Many expect it to be around $ 50,000 per affected.

JOSEPH MAUD

When Joseph Maud was a child urinating on the bed, the nun in charge of his bedroom forced him to rub his face against the dirty sheets.

"It was very degrading, humiliating, because I was in a dormitory with 40 other children, it makes me cry at this moment when I think about it, but the biggest pain was being separated from my parents, my cousins and my uncles", Maud said in 2015 to the BBC when recalling that traumatic experience that he had to live in the mid-1960s.

Maud was one of the 150,000 aboriginal children who, between 1840 and 1996, the Canadian government forcibly separated from their families and sent them internees managed by the Catholic Church.

The children were forbidden to speak their own languages or practice their native culture. They were not casual decisions: the goal was to force their assimilation into Canadian society, as understood by the Anglo-French majority. The idea was "to kill the Indian in the child".

More than 6,000 children died in those schools. Many suffered emotional, physical and sexual abuse, according to the report presented in 2015 by the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation of Canada (CTR), which gathered the testimony of more than 7,000 people about what happened in those schools.

Some of the survivors blame that traumatic experience for the high incidence of problems of poverty, alcoholism, domestic violence and suicide that exist in their communities today.

The report described what happened as "cultural genocide."

"These measures were part of a coherent policy to eliminate Aborigines as different peoples and assimilate them into the majority of Canadian society against their will," the document says.

"The government of Canada applied this policy of cultural genocide because it wanted to separate itself from legal and financial obligations with the aboriginal peoples and obtain control over their lands and resources," he adds.

JOSEPH MAUD

When Joseph Maud was a child urinating on the bed, the nun in charge of his bedroom forced him to rub his face against the dirty sheets.

"It was very degrading, humiliating, because I was in a dormitory with 40 other children, it makes me cry at this moment when I think about it, but the biggest pain was being separated from my parents, my cousins and my uncles", Maud said in 2015 to the BBC when recalling that traumatic experience that he had to live in the mid-1960s.

Maud was one of the 150,000 aboriginal children who, between 1840 and 1996, the Canadian government forcibly separated from their families and sent them internees managed by the Catholic Church.

The children were forbidden to speak their own languages or practice their native culture. They were not casual decisions: the goal was to force their assimilation into Canadian society, as understood by the Anglo-French majority. The idea was "to kill the Indian in the child".

More than 6,000 children died in those schools. Many suffered emotional, physical and sexual abuse, according to the report presented in 2015 by the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation of Canada (CTR), which gathered the testimony of more than 7,000 people about what happened in those schools.

Some of the survivors blame that traumatic experience for the high incidence of problems of poverty, alcoholism, domestic violence and suicide that exist in their communities today.

The report described what happened as "cultural genocide."

"These measures were part of a coherent policy to eliminate Aborigines as different peoples and assimilate them into the majority of Canadian society against their will," the document says.

"The government of Canada applied this policy of cultural genocide because it wanted to separate itself from legal and financial obligations with the aboriginal peoples and obtain control over their lands and resources," he adds.

Although in 2008, the then Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper apologized to the survivors of what happened in these schools, the report points out that there is an urgent need for reconciliation and that the country must move from apologies to action.

On Monday, Harper's successor in charge of the government of Canada, Justin Trudeau, took a step in that direction by asking Pope Francis to apologize for the role of the Catholic Church within those schools in which Aboriginal children suffered countless abuses

"I told him how important it is for Canadians to move towards true reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples and I highlighted how he could help by issuing an apology," Trudeau told reporters after leaving the meeting with the pontiff at the Vatican.

The issuance of an apology by the Pope is one of the measures proposed by the CTR as part of the process of healing the survivors.

Although the Vatican did not comment on Trudeau's request, it did confirm that Francisco had a "cordial" talk for about 36 minutes with the Canadian president and that the conversation "focused on the issues of integration and reconciliation, as well as in religious freedom and ethical issues."

Trudeau, who personally apologized to the survivors, noted that Pope Francis had already offered a similar apology for the ill-treatment suffered by Aboriginal communities in South America during the colonial era.

In 2009, Francisco's predecessor, Benedict XVI, expressed his sorrow for the abuses committed in Canada.

Thank you for taking a little of your valuable time and reading this publication and I hope it is of interest to you. place if you have, any constructive criticism, comments of interest or contributions to the content, if you liked give me favorable upvoto. Regards.

Nice content. Lot of hard work.

IT IS INFORMATION THAT FINDS ON THE INTERNET AND IT SEEMS VERY INTERESTING AND I PUBLISH IT WITH SOME COMMENTS

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_residential_school_system/

Congratulations @dipietrantonio! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Congratulations @dipietrantonio! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!