An Alpha and an Omega

Having looked at various models of Biblical history—both mainstream and alternative—I now turn to the task of building my own model. One possible way of going about this is to establish two firm dates, one at either end of the relevant period, to which the entire timeline can be anchored. In this article and the following one I will seek such an Alpha and Omega for the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

In Search of the Exodus

The defining event in the history of the ancient Israelites is surely the Exodus. This epochal moment is recounted daily in Jewish prayers and re-enacted symbolically at Passover. The story is so well known that I shall not insult you by retelling it.

But did the Exodus even take place?

Most histories of ancient Israel no longer consider information about the Egyptian sojourn, the exodus, and the wilderness wanderings recoverable or even relevant to Israel’s emergence ... Most important is the fact that no clear extrabiblical evidence exists for any aspect of the Egyptian sojourn, exodus, or wilderness wanderings. This lack of evidence, combined with the fact that most scholars believe the stories about these events to have been written centuries after the apparent setting of the stories, leads historians to a choice ... admit that, by normal, critical, historical means, these events cannot be placed in a specific time and correlated with other known history, or claim that the stories are believable historically on the basis of inference, potential connections, and general plausibility. (Moore & Kelle 81)

So, even today in the 21st century there are still a few mainstream scholars who argue for an historical Exodus—the British Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen is perhaps the best known—but they represent an ever-dwindling minority. These scholars have had to greatly reduce the scale of the event in order to explain why there is so little archaeological evidence in favour of it:

The Mediterranean littoral was heavily used by the Egyptian army during the New Kingdom, and the remainder of Sinai shows little evidence of occupation for virtually the entire second millennium BCE, from the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age to the beginning of the Iron Age or even later. Even the site currently identified with Kadesh-barnea provides no evidence of habitation prior to the establishment of the Israelite monarchy. (Redmount, in Coogan et al 77)

The archaeologists may not have found any evidence of the Exodus in the 2nd millennium, but were they looking in the right time frame? If an historical Exodus took place, its only plausible location in the timeline of the Short Chronology lies in the 1st millennium.

An alternative approach to this problem is to find an historical analogue for the Exodus in the history of Egypt, an event that may represent the kernel of truth in the Biblical myth. Curiously, there is an event in Egyptian history that is remarkably similar to the Exodus, so much so that even skeptics cannot ignore it:

Counterparts, general or specific, to the Israelite “Exodus from Egypt” are more difficult to establish ... The closest historical parallel to the Israelite departure from Egypt, and the only known comparatively large-scale exodus of Asiatics from Egypt, is the expulsion of the Hyksos that marked the end of the Second Intermediate Period and the beginning of the New Kingdom. In fact, the Hyksos provide the only historical parallel that incorporates all three major elements of the biblical Exodus narrative—descent, sojourn, and departure ... (Redmount, in Coogan et al 76)

The expulsion of the Hyksos sounds so like the Biblical Exodus that it was actually identified with the Exodus almost two thousand years ago by the Jewish historian Josephus:

Tutimaeus: In his reign, for what cause I know not, a blast of God smote us; and unexpectedly, from the regions of the East, invaders of obscure race marched in confidence of victory against our land. By main force they easily seized it without striking a blow; and having overpowered the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of the gods, and treated all the natives with a cruel hostility, massacring some and leading into slavery the wives and children of others ... Their race as a whole was called Hyksos, that is king-shepherds ... These kings dominated Egypt, according to Manetho, for 511 years. Thereafter, he says, there came a revolt of the kings of the Thebaid and the rest of Egypt against the Shepherds, and a fierce and prolonged war broke out between them. By a king whose name was Misphragmuthosis, the Shepherds, he says, were defeated, driven out of all the rest of Egypt, and confined in a region ... by name Auaris. According to Manetho, the Shepherds enclosed this whole area with a high, strong wall, in order to safeguard all their possessions and spoils. Thummosis, the son of Misphragmuthosis (he continues), attempted by siege to force them to surrender, blockading the fortress with an army of 480,000 men. Finally, giving up the siege in despair, he concluded a treaty by which they should all depart from Egypt and go unmolested where they pleased. On these terms the Shepherds, with their possessions and households complete, no fewer than 240,000 persons, left Egypt and journeyed over the desert into Syria. There, dreading the power of the Assyrians who were at that time masters of Asia, they built in the land now called Judaea a city large enough to hold all those thousands of people, and gave it the name of Jerusalem. (Josephus, Against Apion 1:75-90)

Josephus’s source for this history was Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, a Greek history of Egypt written by an Egyptian priest for the Macedonian Ptolemies. In the first article in this series, Making History, I mentioned some of the shortcomings of this work. Manetho is suspected of magnifying the history of his country beyond the bounds of credibility. When, however, he describes Egypt’s humiliating occupation by a race of cruel foreigners, there are fewer grounds for skepticism. Only fragments of the Aegyptiaca survive, and it is to Josephus that we owe the existence of the preceding passage.

There are, however, more ancient Egyptian records of the subjugation of the country by the Hyksos and their subsequent expulsion. The celebrated Egyptologist James Henry Breasted briefly summarizes this period of Egyptian history in these words:

The fall of the Twelfth Dynasty in 1788 B. C. was followed by a second period of disorganization and obscurity, as the feudatories struggled for the crown. Now and then an aggressive and able ruler gained the ascendency for a brief reign, and under one of these the subjugation of Upper Nubia was carried forward to a point above the third cataract; but his conquest perished with him. After possibly a century of such internal conflict, the country was entered and appropriated by a line of rulers from Asia, who had seemingly already gained a wide dominion there. These foreign usurpers, now known as the Hyksos, after Manetho’s designation of them, maintained themselves for perhaps a century. Their residence was at Avaris in the eastern Delta, and at least during the later part of their supremacy, the Egyptian nobles of the South succeeded in gaining more or less independence. Finally the head of a Theban family boldly proclaimed himself king, and in the course of some years these Theban princes succeeded in expelling the Hyksos from the country, and driving them back from the Asiatic frontier into Syria. (Breasted 1905:17)

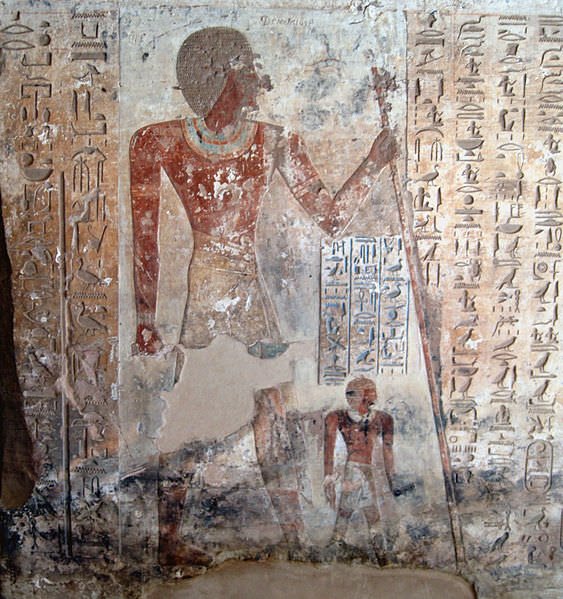

In his Ancient Records of Egypt, Breasted draws attention to an inscription from the time of Ahmose I, the founder of the 18th dynasty and the Pharaoh credited with liberating Egypt from the Hyksos. The inscription, on the wall of a cliff-tomb at El Kab, is the biography of a naval officer who served under three Pharaohs, including Ahmose, whose name he shared:

After an introduction and a few words about his youth and parentage, Ahmose plunges directly into his first campaign, with an account of a siege of the city of Hatwaret (ḥ·t-w‘r·t). This can be no other than the city called Avaris by Manetho (Josephus, Contra Apion, I, 14), where, according to him, the Hyksos make their last stand in Egypt ... The siege, which must have lasted many years, was interrupted by the rebellion of some disaffected noble in Upper Egypt; but the city was finally captured, and the Hyksos, fleeing into Asia, were pursued to the city of Sharuhen (Josh. 19:6). Here they were besieged for six years by Ahmose I, and this stronghold was also captured. (Breasted 1906:2:4-5)

Breasted also draws attention to an inscription which Ahmose I’s great-granddaughter Hatshepsut left in the temple of Pakhet at Speos Artemidos:

In this remarkable document the energetic queen has left a record of her systematic restorations in the temples which had been desolated by the barbarities of the Hyksos, and had remained so down to her reign ... Its references to the Hyksos coincide remarkably with the account of their treatment of the temples as recorded by Manetho. The Hyksos are called “Asiatics” (‘’mw), and their city is “Avaris (ḥ·t-w‘r·t) of the Northland .” (Breasted 1906:2:122)

In the mainstream chronology, the expulsion of the Hyksos is now dated to about 1550 BCE, which is considered too early for the Exodus. So the archaeologists have been looking for the Exodus in a later period of Egyptian history, such as the 19th dynasty (which they place around 1200 BCE). But what does the Short Chronology have to say about the Hyksos?

Gunnar Heinsohn and the Hyksos

Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen, is one of the pioneers of the Short Chronology. An economist by education, in the 1980s he began to study ancient history and quickly came to the conclusion that the chronology taught in textbooks was at odds with the stratigraphic record. Heinsohn believes that civilization arose in the Near East around 1200 BCE. Most of his papers are in German, and English translations are thin on the ground. Being an outsider, Heinsohn has of course been shunned by mainstream academia. It was bad enough being lectured on ancient history by a psychiatrist (Velikovsky)—but an economist!

One of Heinsohn’s most brilliant insights is the concept of the triplication of ancient history. Here is how his disciple, Emmet Sweeney, describes this idea:

The chronology of the ancient Near East was put together using three quite separate dating blueprints, each a replica of the other, which produced in the end an actual triplication of ancient history. There was the history of the region known to the classical authors, covering the first millennium BC, which was in fact the true history of the region. A duplicate history, placed in the second millennium, was then supplied by applying material from Egypt, and another phantom history, this time placed in the third millennium, was supplied by cross-referencing with Mesopotamian material. Thus the Akkadians of the third millennium are in fact stratigraphically contemporary with (and identical to) the Hyksos of the second millennium; and both are one and the same as the Assyrians of the first millennium BC. (Sweeney 76)

Heinsohn, then, concluded that the Akkadians, the Imperial Assyrians and the Hyksos were one and the same people. The Akkadian Empire of supposedly 2300-2100 BCE, the Old Assyrian Empire of 2000-1400 BCE and the Hyksos Kingdom of 1650-1550 BCE were actually the same empire, which belonged to a period of history much closer to the present time (roughly 900-700 BCE).

Josephus, citing Manetho, clearly distinguishes the Hyksos from the Assyrians. But it is worthy of note that he synchronizes their expulsion from Egypt with the height of Assyrian power in Asia:

Finally [the Hyksos] made one of their number, named Salitis, king. He resided at Memphis, exacted tribute from Upper and Lower Egypt, and left garrisons in the places most suited for defence. In particular he secured his eastern flank, as he foresaw that the Assyrians, as their power increased in future, would covet and attack his realm ... [The Hyksos] left Egypt and traversed the desert to Syria. Then, terrified by the might of the Assyrians, who at that time were masters of Asia, they built a city in the country now called Judaea, capable of accommodating their vast company, and gave it the name of Jerusalem. (Josephus 1:77 ... 89-90)

Josephus clearly believed that the Hyksos were the ancient Israelites. That is not what the Short Chronologists believe. According to Heinsohn and Sweeney the Hyksos were Assyrians : the Israelites and other Semitic peoples were their clients and allies. When the Assyrians were expelled from Egypt, their allies were also obliged to leave, so the Biblical Exodus was merely one chapter in the history of the Hyksos expulsion. This is actually in agreement with the Bible, which explicitly states that the Israelites were accompanied on the Exodus by a mixed multitude of non-Israelites:

And the children of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Succoth, about six hundred thousand on foot that were men, beside children. And a mixed multitude went up also with them; and flocks, and herds, even very much cattle. (Exodus 12:37-38)

But when did all this take place?

Dating the Exodus

While Sweeney agrees with Heinsohn’s Hyksos-Assyrian equation, he does not believe that the Biblical Exodus occurred at the time of the Hyksos expulsion. Sweeney places the Exodus around 850 BCE, half a century before the Hyksos invaded Egypt. On this point, I disagree with him. As a working hypothesis, I accept the synchronism of the Exodus and the expulsion of the Hyksos. The latter is the only event in Egyptian history that can account for something as epochal as the Exodus. In this regard, I am in complete agreement with another prominent proponent of the Short Chronology, Charles Ginenthal. Although Ginenthal is an avowed disciple of Immanuel Velikovsky, he has always been prepared to revise Velikovsky’s theories in the light of new evidence:

Velikovsky in Worlds in Collision maintained that the Earth had undergone two periods of celestial catastrophes. The first two events occurred around 1500-1400 B.C. ... The second period of catastrophes was lower in its destructiveness, and these occurred around 800 to 700 B.C. ... One of Velikovsky’s major themes was that of the Venus near-collision with Earth around 1500-1400 B.C. in which the Hebrew slaves in Egypt left that land after a series of catastrophes. Since the short chronology only allows high civilization to arise about 1200-1100 B.C., Velikovsky’s chronology cannot be historically or scientifically correct. Heinsohn, on the other hand, sets the Exodus in Hyksos/Akkadian/Assyrian times in the 8th century B.C. with the Hebrew host as allies to the Hyksos. Thus, the catastrophe, related not only to the ones described above ranging across the ancient world, which brought down a great number of cities, towns, and villages via earthquakes, floods, and fires, had to have also been the same one related in the chronicle of the biblical Exodus. (Ginenthal 2010:440 ... 440 ... 505)

Velikovsky anchored the second series of catastrophes between 776 and 687 BCE. In the Short Chronology, this is roughly where we must place the Exodus—at least as a working hypothesis. But can we do any better?

Pinning Down the Exodus

According to the Book of Exodus, the Israelites were guided on their way through the wilderness by a pillar of cloud during the day and by a pillar of fire during the night:

And the Lord went before them by day in a pillar of a cloud, to lead them the way; and by night in a pillar of fire, to give them light; to go by day and night: He took not away the pillar of the cloud by day, nor the pillar of fire by night, from before the people. (Exodus 13:21-22)

Charles Ginenthal is not the first person to suggest that these bright pillars might have been a comet:

... the people crossing the Sinai would have arrived there around June, after three-months—three new moon periods—which brings us to the pillar of light in the sky by day and of fire by night which was probably a comet, Halley’s Comet, another somewhat common event dated to 763 B.C. Duncan Steel dates the apparition of Halley’s Comet tentatively to August of 763 B.C. (Ginenthal 2010:542)

Here Ginenthal refers us to Marking Time by the British astrophysicist Duncan Steel. Steel discusses an eclipse of the Sun that is mentioned several times in the Bible, including Job 9:6-7. Following the conventional chronology, Steel identifies this event with a solar eclipse that is tentatively dated to 15 June 763 BCE. In Volume 2 of his Pillars of the Past, Ginenthal discusses this eclipse at some length (Ginenthal 2008:164-185). Steel also wrote about this event in his earlier work Eclipse, which is available on the Internet Archive:

Various events around 760 B.C., culminating in a major earthquake that damaged Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem and caused a huge destructive wave in the Sea of Galilee, clearly had a considerable effect upon the people of Judea. The fact that the rumble was felt over 800 miles away allows us to estimate that the tremble was about magnitude 7.3 on the Richter scale. In the Bible there are eight separate allusions to a solar eclipse around that time, which may be identified as June 15, 763 B.C. We are told the eclipse was followed closely by a bright comet. If this was Halley’s Comet (we cannot be sure due to the sparsity of the information) then we know from a backwards extrapolation of its orbit that the comet indeed would have been visible in August of 763 B.C., five centuries before the earliest definite observation cited above. (Steel 2001:20)

Steel, then, has suggested that this bright comet was none other than Comet Halley, the most famous comet of them all. Of course, Steel believes that the earthquake, eclipse and cometary apparition all happened more than half a millennium after the Exodus, but Ginenthal is happy to draw the conclusion that the famous pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night was Halley’s Comet. It is a bit of a stretch, I admit, and a thin thread on which to pin our chronology, but 763 is close to where most Short Chronologists would like to place the Exodus.

Let us, therefore, tentatively anchor the Biblical Exodus (and the Expulsion of the Hyksos) to the year 763 BCE, and see where that gets us.

To be continued ...

References

- Megan Bishop Moore, Brad E Kelle, Biblical History and Israel’s Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2011)

- Michael D Coogan (editor), The Oxford History of the Biblical World, Oxford University Press, Inc, New York (2001)

- Josephus, H St J Thackeray (editor, translator), Against Apion, Loeb Classical Library L186, William Heinemann, London (1926)

- James Henry Breasted, A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York (1905)

- James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Volumes 1-5, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1906)

- Charles Ginenthal, Mesopotamian, Anatolian, Mycenaean, Minoan, and Harappan Chronology, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, New York (2008)

- Charles Ginenthal, Egypt and Palestine, Pillars of the Past, Volume 3, Forest Hills, New York (2010)

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Genesis of Israel and Egypt, Ages in Alignment, Volume 1, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Worlds in Collision, Macmillan Publishers, New York (1950)

- Duncan Steel, Marking Time: The Epic Quest to Invent the Perfect Calendar, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, New York (2000)

- Duncan Steel, Eclipse: The Celestial Phenomenon that Changed the Course of History, The Joseph Henry Press, Washington DC (2001)

Image Credits

- The Crossing of the Red Sea: Wikimedia Commons, Nicolas Poussin (artist), Public Domain

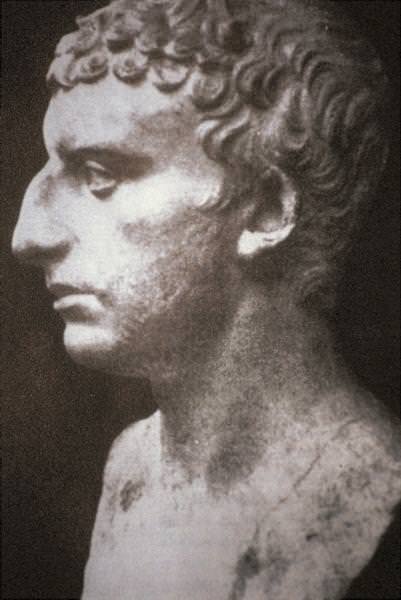

- Bust of Josephus?: Wikimedia Commons, Anonymous, 1st Century, Public Domain

- James Henry Breasted: Wikimedia Commons, Chicago Daily News, Public Domain

- Tomb of Ahmose Son of Ebana: Wikimedia Commons, © Olaf Tausch, Creative Commons License

- Gunnar Heinsohn: Wikimedia Commons, © Freud, Creative Commons License

- Emmet J Sweeney: © Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (SIS), Fair Use

- Charles Ginenthal: © Dwardu Cardona, Fair Use

wow nice your post

Before your post i have no idea about this history. Thanks for sharing.

What a wonderful publication, it is very informative and despite how extensive it is, it is very well summarized and easy to understand, very great work my dear friend @harlotscurse, Many blessings from Venezuela and to follow the good content in Steemit!

very nice history my friend @harlotscurse i like post

A great research that leads us to reflect and question many things, excellent.

Very good article and yeah you have created a quality content about history ..well explained everything☺

I love talking about this kind of topics with my friends, they are too exciting, very good post My Lord, In search of the Exodus is a fascinating story, great work

wow...what a beautiful history dear friend @harlotscurse

thanks for share

Really Its a great publication. Excellent writing.

A great work of the time of the painter, many years ago it is worthwhile to admire almost all his works. regards