The Screen Addict | Tony Scott

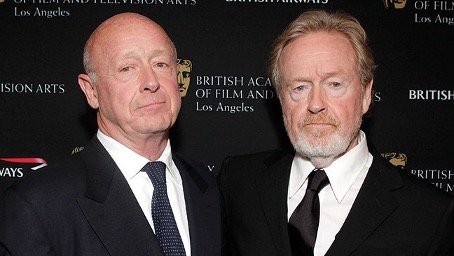

In an earlier blog, I wrote about my deep affection for Ridley Scott’s Black Rain (1989). It is absolutely true – the elder Scott is first responsible for my undying love for film. His younger brother Tony however, is a close second.

Tony Scott jet-engined to the very top of the pop-culture echelons on the strength of his big-screen debut Top Gun (1986). True film-buffs will know that I am bending the truth here just a little bit – Scott actually made his entry into the world of feature films three years earlier, with the stylish but little-seen David Bowie vampire-flick The Hunger (1983). TG however, catapulted the director and a young up-and-coming actor named Tom Cruise into superstardom.

I have to admit I was never a big fan of TG. It is very much a Tony Scott film though, and it has my enduring admiration for kickstarting the hugely entertaining and extremely profitable Simpson / Bruckheimer High-Concept Hollywood reign. The film that made me notice Scott however, was the sequel to another Simpson / Bruckheimer production about a fast-talking Detroit Cop stirring up Beverly Hills.

I have written at length on this forum about my appreciation of strong opening-sequences, and the one leading into Beverly Hills Cop II (1987) is among the greatest ever secured on film. As always, the soundtrack is an integral part of the efficacy of the sequence and crucially, BHCII jumps right into the action by cueing the music to Paramount’s company logo. Please see for yourself, because visuals sometimes speak louder than words:

I can’t stress enough how important I think it is to be sucked into a story this way. Sure, the Alphabet Lady looks a little cartoonesque compared to contemporary villains, but this was 1987 and the idea of Brigitte Nielsen pulling heists was just freakin’ awesome.

What’s more – the sequence isn’t cool just because it features a six-foot blonde executing the perfect smash and grab, it works mostly on the strength of Scott’s completely original approach to directing Action. No other filmmaker at the time could bring that level of dynamics to a scene. It is the perfect marriage of directing, editing and scoring. And yes, the tremble in Nielsen’s voice is a nice piece of acting, too.

BHCII is by no means a perfect film. It bothers me greatly for example, that Murphy’s Ferrari switches between a model 308 and 328. The same distracting thing happens to the bad guys’ Camaro and limousine – after the vehicles crash, they mysteriously morph into an earlier model. I am sure this was the result of budget restrictions, but it has always struck me as odd that a meticulous director like Tony Scott would accept such flaws in his body of work.

These minor mistakes that only a complete nerd like me would notice, don’t take anything away from the pure cinematic joy that is BHCII. At the time, the cynical view of most “critics” was that the film was an uninspired rush job, produced only to cash in on the success of the original. My personal experience was quite the opposite, however. I actually saw BHCII before I discovered the first installment – the same thing happened with Aliens (1986) and Alien (1979) – and it made an indelible impression on the ten-year-old me.

People forget what a force of nature Eddie Murphy was. After laying low for years, the actor only recently revived his surefire brands with Coming 2 America (2021) and an upcoming fourth installment in the Beverly Hills Cop series. But during The Eighties and early Nineties, Murphy was the King of Hollywood. He was the man who single-handedly guaranteed the bottom line of Paramount Pictures, the studio that released all of his films. During the pinnacle of his career, it indeed felt like there was no other star than Eddie “Money” Murphy, and BHCII was my favorite of his films.

Being mildly obsessive-compulsive, I would rent a film that I liked over and over again. Back then there were no on-demand services, so the only way to re-watch something you liked, was a visit to the local rental store. With BHCII, my focus started to shift from Murphy’s antics to the way certain scenes were executed. Why did I get so excited about the lighting in the scene that sees the Ferrari fly into the streets of Detroit? How did the gunfire in BHCII have so much more impact when compared to similar sequences in other action films? It started to dawn on me that it had to have something to do with the person who is always the last one mentioned in the opening credits.

After BHCII, I became a student of Tony Scott, devouring everything he had done so far. TG, BHCII and other Eighties staples like Revenge (1990) and Days of Thunder (1990) had made the director one of the most sought-after filmmakers of the time, and soon more era-defining films followed. During The Nineties, Scott made some of his more polarizing films, always toeing the line between avant-garde artiste and savvy commercialist.

By far his most revered work from this decade, is the brilliant Crime-Thriller True Romance (1993). Written by long-time Scott aficionado Quentin Tarantino, the film is an explosion of everything we love about cinema. On top of Tarantino’s on-of-a-kind script, TR features an unforgettable Hans Zimmer score, amazing photography by Scott’s go-to cinematographer Jeffrey Kimball, and an absolutely unprecedented cast list. I dare you to find another film that comes even close to this stellar line-up – Christian Slater, Patricia Arquette, Dennis Hopper, Gary Oldman, Christopher Walken, Samuel L. Jackson, James Gandolfini and Val Kilmer and Brad Pitt... It’s like the filmmakers stole Michael Ovitz’ rolodex and just went to town.

The synergy of pure talent that is TR, culminates in an unforgettable scene that will forever be one of my favorites from Scott’s filmography. Frankly, I think it is one of the best sequences ever to be trusted to celluloid:

Everything is in sync here – Tarantino’s raw, edgy script, Walken and Hopper’s pitch-perfect delivery of the dialogue, Scott’s meticulous direction (see how he cuts to Gandolfini’s smug face a couple of times and how it enhances the tension) and the perfect timing of Léo Delibes’ Lakmé. It is truly a master-class of filmmaking.

Next in Scott’s filmography is Crimson Tide (1995), which is by far my favorite film by the director. This superb submarine Thriller came out during an explosive resurgence of the sub-genre. Hollywood has a long tradition of U-boat pictures – some of ‘em are even specifically mentioned in CT – but The Nineties and early Aughts were exceptionally rich on the subject. Within the timeframe of a couple of years, we were treated to the likes of The Hunt for Red October (1990), U-571 (2000), Below (2002) and K-19: The Widowmaker (2002) – not to mention the Comedy-angled Down Periscope (1996).

What sets CT apart in my opinion, is the match made in heaven that is Tony-Tarantino. Although originally written by Michael Schiffer, Scott asked his trusty TR collaborator to “Tarantino-ize” the dialogues. It was never revealed which lines exactly came from Quentin’s pen – both Robert Towne and Steven Zaillian reportedly also did some script doctoring – but to me the film feels very similar to the audiovisual fireworks on display in TR:

Scott expected to get full cooperation from the Navy on CT – like he got on TG years before – but the US Government was not so keen this time. What makes the film so nail-bitingly exhilarating – two senior officers disagreeing on how to interpret an apparent order to launch nuclear missiles – is exactly what disturbed the actual armed forces. The US Navy decided it was bad publicity to support a production wherein mutiny was on full display, and publicly disavowed the film.

The premise is utterly fascinating to me, though. Jason Robards – in a cameo as a naval inquirer in CT’s final scene – says it best: “…you were both right, and you were also both wrong.” It is, to an extent, very similar to the central issue in another one of my all-time favorites – A Few Good Men (1992). Do you blindly follow orders or are you, under certain circumstances, allowed and perhaps even expected to question them? It is a topic for an extremely complicated discussion that will occupy the minds of men and inform film scripts for years to come. Not to mention an opportunity to organize the ultimate themed movie-night with a double presentation of CT and AFGM…

After CT, Scott made a series of films that wildly divided fans and critics alike. The one that we are absolutely, under no circumstances, allowed to like according to the people who claim there is such a thing as a bad film, is The Fan (1996). It gives me great pleasure to wholeheartedly disagree with the folks who confuse their own taste with that of the rest of the world. I adore The Fan.

Again, the combination of crucial elements is spot on here – a stellar cast consisting of Robert De Niro, Wesley Snipes, John Leguizamo, Ellen Barkin and Benicio Del Toro, moody cinematography by CT lenser and future Ridley Scott collaborator Dariusz Wolski, and a haunting Hans Zimmer score. Zimmer was by then a Scott trustee, providing the soundtrack for most of Tony and Ridley’s films.

I struggle to understand why there is so little love for The Fan. As he did so many times before, Scott blazed the trail for numerous young directors who came after him with stylistic choices that are still used to this day. Although it is debatable which prolific filmmaker first thought of Trent Reznor as a fantastic audio contributor to their visuals (Tony Scott, Oliver Stone or David Fincher), the composer certainly appears to be more in demand since The Fan, Natural Born Killers (1994) and Se7en (1995).

The Fan also was Scott’s self-confessed experimental film that led into his phase of increasingly frenetic editing. I personally feel that Scott pushed the cutting of his films into the extreme after The Fan, climaxing – or cratering, as you please – with Domino (2005), but I did always appreciate the sheer originality of it.

After The Fan came, among other projects, four more films with CT star Denzel Washington. I ran to the cinema for every single one of ‘em, and recognized the master’s hand time and time again. Man on Fire (2004) is widely regarded as Scotts’s Magnum Opus, and Tarantino recently named Unstoppable (2010) as one of his favorite films of the last decade. I love all of Scott’s work, but my heart truly belongs to the films he made before Enemy of The State (1998).

On August 19th 2012, Tony Scott committed suicide by jumping of the Vincent Thomas Bridge in Los Angeles. I honestly don’t know what to write after a devastating sentence like that. Scott’s films gave me more joy than any other director I can think of, and I am selfishly sad that there won’t be any more. His older brother Ridley continues to make masterpiece after masterpiece, and shows no signs of slowing down any time soon. I have never seen or heard Ridley speak publicly about his brother’s death, and he is of course not obligated to do so. Tony Scott’s untimely demise remains one of the most frustrating events in film history though, and all I can do is quietly celebrate the man and his work.

I think I will rewatch The Fan tonight…

#thescreenaddict

#film

#movies

#contentrecommendation

#celebrateart

#nobodyknowsanything

Twitter (X): Robin Logjes | The Screen Addict