I materiali dell'Architettura: I materiali metallici - Terza Parte// Materials of Architecture: Metallic materials - Third Part [ITA - ENG]

CCO Creative Commons Torre Eiffel, Parigi

torniamo a parlare dei materiali metallici. Fino ad oggi abbiamo visto cosa siano e quali siano state le loro origini ed applicazioni e, a questo riguardo, abbiamo imparato che, seppur si sia fatto largo uso dei metalli sin dai tempi antichi, per la loro applicazione al mondo delle costruzioni si è dovuto attendere, fatta qualche rara eccezione, fino al XVIII secolo.

Ecco, ed è proprio da qui che oggi ripartiamo. Vedremo come l’avvento di materiali come ferro, ghisa e acciaio abbiano ancora una volta rivoluzionato il mondo dell’architettura e dell’ingegneria e come quest’ultima, dato il grande e continuo progresso in campo tecnico, finisce col prevalere sull’architettura… insomma, se volete saperne di più, non vi resta che continuare a leggere!

IL GRANDE RUOLO DELL’INGEGNERIA TRA IL XVIII E IL XIX SECOLO

Come più volte abbiamo detto, il XVIII secolo è portatore di grandi cambiamenti nel settore delle costruzioni: l’impiego di materiali ferrosi, infatti, cambia ancora una volta il modo di concepire e di realizzare le costruzioni. Il continuo e veloce progresso al quale si assiste finisce inevitabilmente col mettere in secondo piano la figura dell’architetto in favore della più fiorente professione dell’ingegnere.

Le prime vere e proprie utilizzazioni del ferro come materiale da costruzione si devono ad Abram Darby, un imprenditore inglese, grazie al quale si rese possibile una prima produzione in serie di elementi strutturali metallici. Le prime opere ad essere realizzate in ferro, a sottolineare la continua affermazione del ruolo della tecnica, sono i ponti.

Il primo esemplare di tali opere, l’Iron Bridge, sorge, su progetto di Wilkinson, proprio nei pressi dell’officina di Darby, a Coalbrookdale, sul fiume Severn, intorno al 1775. Non mancano altri illustri esempi, basti pensare al Ponte sul Tamigi di Thomas Telford, risalente al 1801, progettato ma mai realizzato, che prevedeva un’unica struttura ad arco in ghisa per una luce di oltre 180 metri.

Sono diverse le tecnologie impiegate per la realizzazione di queste opere. Prendendo i due esempi appena citati, il primo, sul fiume Severn, prevedeva l’impiego di grossi pezzi costituiti da semiarchi, il secondo, quello sul Tamigi, prevedeva invece l’impiego di un gran numero di conci in ghisa, vuoti internamente e dunque più leggeri, assemblati analogamente ai cocci in pietra, consentendo di coprire luci notevolmente maggiori rispetto al primo.

Nel campo dell’edilizia la ghisa trovava sempre più diffusione e infatti, nel 1801, venne realizzata la prima struttura con travi e pilastri interamente in ghisa, destinata ad una Filanda per il cotone, progettata da Boulton e Watt.

Verso la metà del XIX secolo, il continuo sperimentare in ambito tecnico porta ad un nuovo tipo edilizio, il padiglione per le esposizioni universali, pensato per delle grandiose fiere che venivano organizzate dai paesi all’avanguardia nel settore industriale.

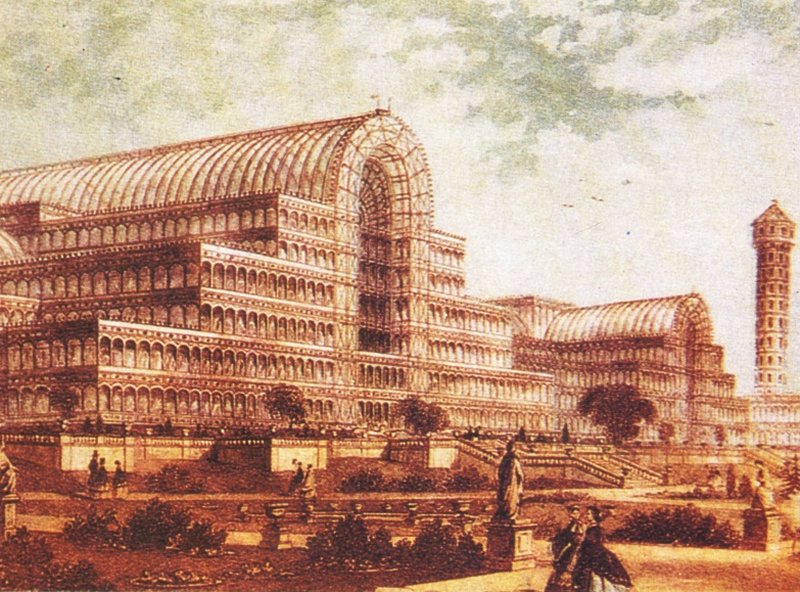

Protagonisti di questo ambito della progettazione furono, fra gli altri, l’inglese Joseph Paxton e il francese Victor Contamin. Il primo, in occasione della prima Grande Esposizione di Londra, nel 1851, realizzò il Palazzo di Cristallo, prototipo delle grandi opere realizzate con elementi prefabbricati, quali segmenti di ghisa e lastre in vetro, prodotti in serie e montati in cantiere. Con caratteristiche come la sua assenza di ornamenti o il suo volume trasparente, quest’opera di fatto aprì le porte alla nuova estetica che avrebbe avuto l’architettura contemporanea.

Risale invece all’ Esposizione di Parigi del 1889 l’opera ingegneristica di Contamin, la cosiddetta Galleria delle macchine, questa volta arricchita da un articolato sistema decorativo. Sempre per quest’esposizione venne presentata ed eretta, seppur fra mille polemiche, l’opera di uno dei più geniali ingegneri del XIX secolo, Gustave Eiffel, ovvero la celebre Torre Eiffel, caratterizzata da elementi portanti costituiti dall’unione di piccoli profilati standard, così da conferire all’opera il minimo peso ma, allo stesso tempo, i massimi risultati statici.

In definitiva, dunque, con la Rivoluzione Industriale assistiamo ad un grande punto di svolta nel mondo dell’architettura e dell’ingegneria che, inevitabilmente, cominciano ad assumere due diverse identità: da un lato l’architettura che sembra essere la più creativa e sensibile rispetto ai bisogni contemporanei, e dall’altro l’ingegneria, che invece sembra più legata al progresso tecnologico.

In realtà, però, i due mondi sono sempre interconnessi e talvolta, come sappiamo, l’uno è fonte di ispirazione e miglioramento per l’altro. Sta di fatto che, se da una parte i prodotti dell’ingegneria potevano essere considerati privi di quegli elementi nobili tipici dell’arte e dell’architettura, dall’altra le attività storicamente connesse al modo dell’architettura stavano per diventare superflue al confronto delle grandi abilità e all’energia tipiche invece della sfera ingegneristica.

Insomma, nonostante apparentemente ingegneria e architettura sembrano destinate ad assumere due identità ben diverse, di fatto non si smette mai di cercare il giusto connubio tra le due discipline. Nasce la necessità di combinare l’aspetto naturale, con il tradizionale e con il meccanico: cambiano così i rapporti tra carico e supporto, tra rivestimento e struttura, in particolar modo quando, a fine XIX secolo, si ha la necessità di creare edifici molto sviluppati in altezza, i grattacieli.

Ed è in questo contesto che, rendendo manifesto l’effettivo telaio strutturale, l’interazione tra pilastri, travi, archi, marcapiani, modanature e lastre di vetro, pone le basi per una nuova concezione dell’estetica. Un esempio lampante di questo tentativo di riconciliazione tra architettura e ingegneria lo si evince chiaramente dagli edifici commerciali realizzati nel Midwest nell’ultimo ventennio del 1800, che portarono i costruttori del tempo a confrontarsi sui molti aspetti che questo dualismo tra architettura e ingegneria poneva in evidenza… ma questa, miei cari lettori, è un’altra storia!

E così anche per oggi siamo giunti alla fine del viaggio, naturalmente c’è ancora molto da raccontare sui materiali ferrosi, sulla loro storia e sulla loro tecnologia. Io mi auguro, come sempre, di avervi incuriosito e gradevolmente intrattenuto con questa mia lettura e, sempre che ne abbiate voglia e tempo, come sempre vi rinnovo l’appuntamento al prossimo articolo, vi abbraccio tutti!

L'Ego dice: "Quando ogni cosa andrà a posto troverò la pace".

Lo Spirito dice: "Trova la pace e ogni cosa andrà a posto".

CCO Creative Commons Iron Bridge, Coalbrookdale

let's go back to talking about metallic materials. Until today we have seen what they are and what have been their origins and applications and, in this regard, we have learned that, although they have made extensive use of metals since ancient times, for their application to the construction world was due wait, made some rare exception, until the eighteenth century.

Here, and it is from here that today we leave. We will see how the advent of materials such as iron, cast iron and steel have once again revolutionized the world of architecture and engineering and how the latter, given the great and continuous progress in the technical field, ends up prevailing on architecture... in short, if you want to know more, you just have to keep reading!

THE GREAT ROLE OF ENGINEERING BETWEEN THE XVIII AND THE XIX CENTURIES

As we have said many times, the eighteenth century is the bearer of major changes in the construction industry: the use of ferrous materials, in fact, once again changes the way we conceive and build the buildings. The continuous and rapid progress we are witnessing inevitably ends up by overshadowing the architect's figure in favor of the engineer's most flourishing profession.

The first real uses of iron as a construction material are due to Abram Darby, an English entrepreneur, thanks to whom a first series production of metallic structural elements was made possible. The first works to be made of iron, to underline the continuous affirmation of the role of the technique, are the bridges.

The first example of these works, the Iron Bridge, rises, on a project by Wilkinson, right near the workshop of Darby, in Coalbrookdale, on the river Severn, around 1775 There are other famous examples, just think of the Bridge on the Thames by Thomas Telford, dating back to 1801, designed but never realized, which provided for a single cast-iron arched structure for a light of over 180 meters.

There are several technologies used for the realization of these works. Taking the two examples just mentioned, the first, on the river Severn, provided for the use of large pieces made up of semiarchs, the second, the one on the Thames, provided instead the use of a large number of cast iron segments, empty internally and therefore lighter, assembled similar to the stone shards, allowing to cover significantly greater lights than the first.

In the field of construction, cast iron was becoming increasingly widespread and in fact, in 1801, the first structure was constructed with beams and pillars entirely in cast iron, destined for a Cotton yarn, designed by Boulton and Watt.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the continuous experimentation in the technical field leads to a new type of building, the pavilion for universal exposures, designed for the grandiose fairs that were organized by countries at the forefront of the industrial sector.

The protagonists of this area of design were, among others, the English Joseph Paxton and the French Victor Contamin. The first, on the occasion of the first Great Exposition in London, in 1851, created the Crystal Palace, prototype of the great works made with prefabricated elements, such as cast iron segments and glass plates , mass-produced and assembled on site. With features such as its absence of ornaments or its transparent volume, this work opened the door to the new aesthetic that contemporary architecture would have had.

The engineering work of Contamin, the so-called Gallery of machines, dates back to the Exhibition of Paris of 1889, this time enriched by an articulated decorative system. Also for this exhibition was presented and erected, albeit with a thousand controversies, the work of one of the most brilliant engineers of the nineteenth century, Gustave Eiffel, or the famous Eiffel Tower, characterized from supporting elements consisting of the union of small standard profiles, so as to give the work the minimum weight but, at the same time, the maximum static results.

Ultimately, therefore, with the Industrial Revolution we are witnessing a great turning point in the world of architecture and engineering, which inevitably start to take on two different identities: on the one hand, the architecture that seems to be the most creative and sensitive compared to contemporary needs, and on the other hand engineering, which instead seems more linked to technological progress.

In reality, however, the two worlds are always interconnected and sometimes, as we know, one is a source of inspiration and improvement for the other. The fact is that, if on the one hand the engineering products could be considered devoid of those noble elements typical of art and architecture, on the other the activities historically connected to the architecture way were about to become superfluous when compared to the great skills and energy typical of the engineering sphere instead.

In short, although apparently engineering and architecture seem destined to take on two very different identities, in fact one never ceases to look for the right combination between the two disciplines. The need arose to combine the natural, traditional and mechanic aspect: the relationship between load and support, between cladding and structure changed, especially when, at the end of the 19th century, there was a need to create very developed in height, the skyscrapers.

And it is in this context that, by making manifest the actual structural frame, the interaction between pillars, beams, arches, string courses, moldings and glass sheets, lays the foundations for a new conception of aesthetics. A striking example of this attempt at reconciliation between architecture and engineering is clearly evident from the commercial buildings built in the Midwest in the last two decades of the 1800s, which led the time builders to confront the many aspects that this dualism between architecture and engineering highlighted... but this, my dear readers, is another story!

And so for today we have reached the end of the journey, of course there is still a lot to tell about ferrous materials, their history and their technology. I hope, as always, to have you intrigued and pleasantly entertained with my reading and, as long as you want and time, as always I renew the appointment to the next article, I embrace you all!

The ego says: "When everything goes right I will find peace"

The Spirit says: "Find peace and everything will fall into place"

CCO Creative Commons Palazzo di Cristallo, Joseph Paxton

Le mie fonti...

-Appunti delle lezioni e dei seminari universitari

-William J. R. Curtis, L'architettura moderna dal 1900, Phaidon

-La collana di libri di G.K.Koening-F.Brunetti, Corso di Tecnologia delle Costruzioni , Le Monnier

È impressionante notare quali risultati sono stati ottenuti con tecnologie vecchie di secoli. Tra l'altro se non erro la torre Eiffel doveva essere provvisoria...ma poi mantenuta vista la particolare bellezza.

Scusami se rispondo solo ora comunque, per quel che ne so io, effettivamente la torre Eiffel venne concepita e costruita con la possibilità di essere smontata, come fosse una installazione temporanea per l'Esposizione cui era destinata ma alla fine, come la storia testimonia, divenne opera perenne nonchè simbolo della città! ;)

O era troppo bella, o troppo faticoso smontarla :D

Mamma mia, mi hai riportato indietro di dieci anni, con Joseph Paxton e il palazzo di cristallo! Ti leggo sempre con grande piacere, scopro dei dettagli nuovi ogni volta e faccio un ripasso piacevole quando conosco qualcosa sull'argomento! Il connubio metallo-vetro fu sensazionale nella seconda metà dell'ottocento, soprattutto se pensato in concomitanza con la standardizzazione delle parti e dei componenti: tutto era già preconfezionato, si assemblava in loco, si poteva disassemblare (a meno di ripensamenti). E si creavano delle architetture leggere, alte, luminose. non vedo l'ora di leggere il prossimo articolo, perché parlerai di anni critici! Grazie della bella lettura!

Ti ringrazio tanto e chiedo scusa anche a te per il ritardo nel rispondere! Grazie di cuore per l'interesse per i miei articoli! :)

Upvote