PICTURE GUITAR CHORD: PART 1, CHORD CONSTRUCTION

Hi Steemians, I want share you a compilation and some theory of the guitar chord construction, every single day I will posting a specific chord voicing, and its visual formation, from C trough B°.

WHAT'S A CHORD?

In order to effectively choose and utilize the chords in this post, it is important to have a basic understanding of how chords are constructed. So, what is a chord? A chord is simply defined as three or more notes played at the same time. Typically, its function is to provide the harmony that supports the melody of a song.

HOW DOES A CHORD GET ITS NAME?

A chord gets its name from its root note. For example, the root of a G major chord is G. The remaining notes in the chord determine its quality, or type. This is indicated by the chord suffix. So, in a Bm7b5 chord, B is the root, and m7b5 is the suffix that indicates the quality of the chord.

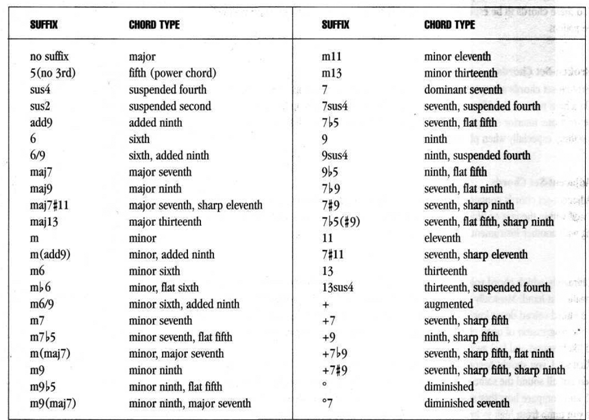

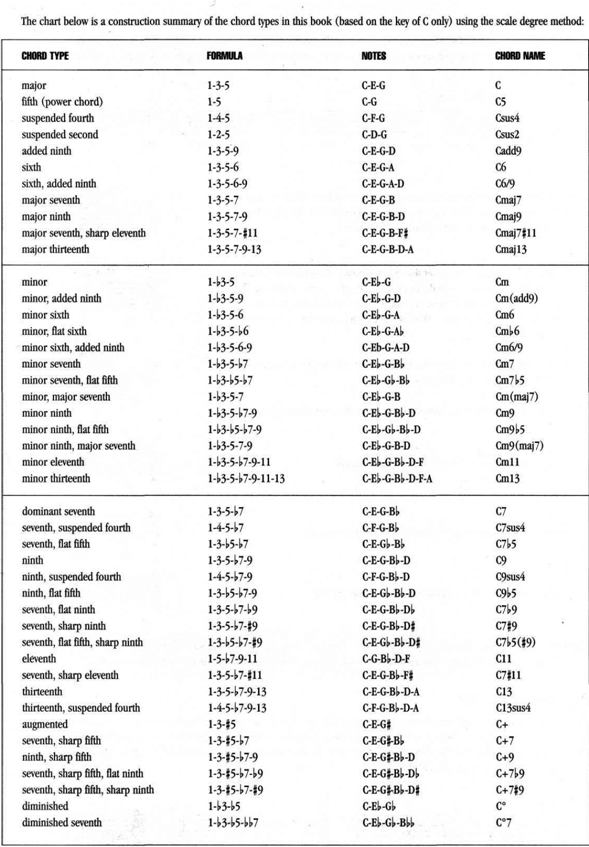

Here a summary table to help you keep track of the suffix for each chord type:

HOW DO I BUILD A CHORD?

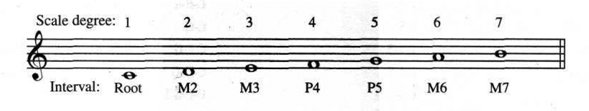

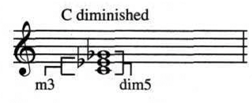

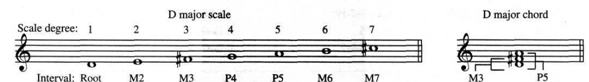

All chords are constructed using intervals. An interval is the distance between any two notes. Though there are many types of intervals, there are only five categories: major, minor, perfect, augmented, and diminished. Interestingly, the major scale contains only major and perfect intervals:

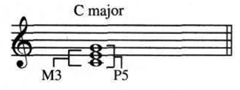

The major scale also happens to be a great starting point from which to construct chords. For example, if we start at the root (C) and add the interval of a major third (E) and a perfect fifth (G), we have constructed a C major chord.

In order to construct a chord other than a major chord, at least one of the major or perfect intervals needs to be altered. For example, take the C major chord you just constructed, and lower the third degree (E) one half step. We now have a C minor chord: C-Eb-G. By lowering the major third by one half step, we create a new interval called a minor third.

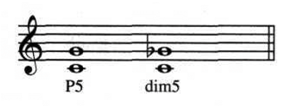

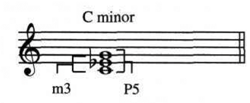

We can further alter the chord by flatting the perfect fifth (G). The chord is now a C°: C-Eb-Gb, the Gb represents a diminished fifth interval.

This leads us to a basic rule of thumb to help remember interval alterations:

A perfect interval lowered one half step is a diminished interval.

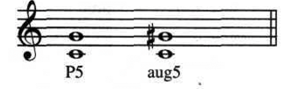

A perfect interval raised one half step is an augmented interval.

Half steps and whole steps are the building blocks of intervals; they determine an interval's quality—major, minor, etc. On the guitar, a half step is just the distance from one fret to the next. A whole step is equal to two half steps, or two frets.

WHAT ABOUT OTHER KEYS?

Notice that we assigned a numerical value to each note in the major scale, as well as labeling the intervals. These numerical values, termed scale degrees, allow us to "generically" construct chords, regardless of key. For example, a major chord consists of the root (1), major third (3), and perfect fifth (5). Substitute any major scale for the C major scale above, select scale degrees 1, 3, and 5, and you will have a major chord for the scale you selected.

TRIADS

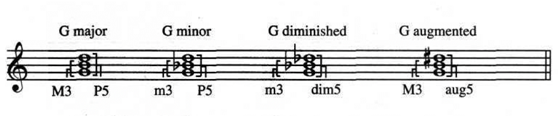

The most basic chords in this book are called triads. A triad is a chord that is made up of only three notes. For example, a simple G major chord is a triad consisting of the notes G, B, and D. There are several types of triads, including major, minor, diminished, augmented, and suspended. All of these chords are constructed by simply altering the relationships between the root note and the intervals.

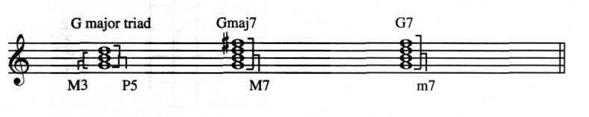

SEVENTHS

To create more interesting harmony, we can take the familiar triad and add another interval: the seventh. Seventh chords are comprised of four notes: the three notes of the triad plus a major or minor seventh interval. For example, if we use the G major triad (G-B-D) and add a major seventh interval (F#), the Gmaj7 chord is formed. Likewise, if we substitute the minor seventh interval (F) for the F#, we have a new seventh chord, the G7. This is also known as a dominant seventh chord, popularly used in blues and jazz music. As with the triads, seventh chords come in many types, including major, minor, diminished, augmented, suspended, and others.

EXTENDED CHORDS

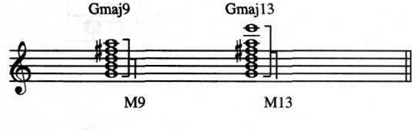

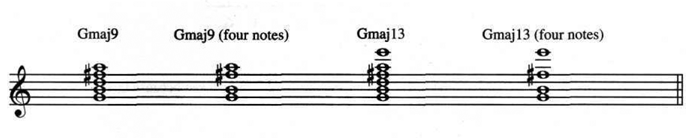

Extended chords are those that include notes beyond the seventh scale degree. These chords have a rich, complex harmony that is very common in jazz music. These include ninths, elevenths, and thirteenth chords. For example, if we take a Gmaj7 chord and add a major ninth interval (A), we get a Gmaj9 chord (G-B-D-F#-A). We can then add an additional interval, a major thirteenth (E), to form a Gmajl3 chord (G-B-D-F#-A-E). Note that the interval of a major eleventh is omitted. This is because the major eleventh sonically conflicts with the major third interval, creating a dissonance

By the way, you may have noticed that these last two chords, Gmaj9 and Gmaj 13, contain five and six notes, respectively; however, we only have four fingers in the left hand! Since the use of a barre chord or open-string chord is not always possible, we often need to choose the four notes of the chord that are most important to play. The harmonic theory that underlies these choices is beyond the scope of this book, but not to worry—it has already been done for you where necessary. Below are two examples to demonstrate these chord "trimmings".

Generally speaking, die root, third, and seventh are the most crucial notes to include in an extended chord, along with the uppermost extension (ninth, thirteenth, etc.).

INVERSIONS & VOICINGS

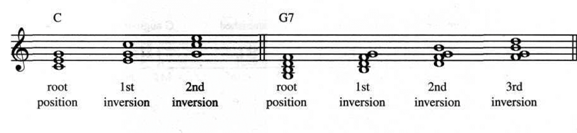

This brings us to our last topic. Though a typical chord might consist of only three or four notes—a C triad, for example, consists of just a root, third, and fifth; a G7 chord consists of a root, third, fifth, and seventh—these notes do not necessarily have to appear in that same order, from bottom to top, in the actual chords you play. Inversions are produced when you rearrange the notes of a chord:

Practically speaking, on the guitar, notes of a chord are often inverted (rearranged), doubled (used more than once), and even omitted to create different voicings. Each voicing is unique and yet similar—kind of like different shades of die same color.

Once again, the possible voicings of a chord are many. The voicings in this post were chosen because they are some of the most popular, useful, and attractive chord voicings playable on the guitar.

Next post:

PICTURE GUITAR CHORD: PART 2, Do (C) CHORDS VOICING

Source:

Guitar chord - Wikipedia

Chord Construction & Chord Formula List

cyberfret

Picture Chord Encyclopedia HAL LEONARD

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://hard-guitar.com/solfeggio-how-to-play-guitar/chords-theory/

This post was builded with my HAL LEONARD book as source