America’s Future Is Texas

hen Frederick Law Olmsted passed through Texas, in 1853, he became besotted with the majesty of the Texas legislature. “I have seen several similar bodies at the North; the Federal Congress; and the Parliament of Great Britain, in both its branches, on occasions of great moment; but none of them commanded my involuntary respect for their simple manly dignity and trustworthiness for the duties that engaged them, more than the General Assembly of Texas,” he wrote. This passage is possibly unique in the political chronicles of the state. Fairly considered, the Texas legislature is more functional than the United States Congress, and more genteel than the House of Commons. But a recurrent crop of crackpots and ideologues has fed the state’s reputation for aggressive know-nothingism and proudly retrograde politics.

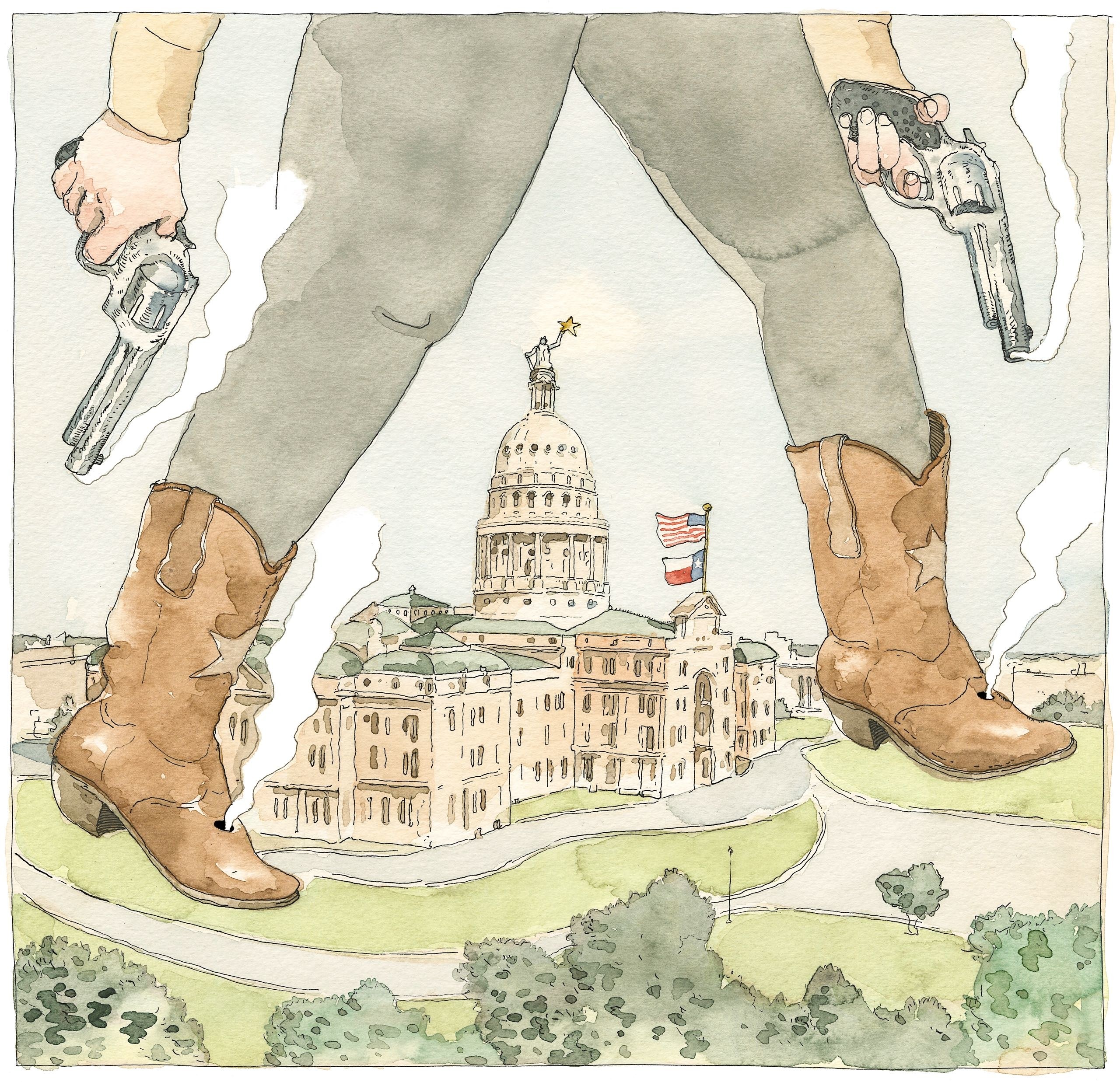

I’ve lived in Texas for most of my life, and I’ve come to appreciate what the state symbolizes, both to people who live here and to those who view it from afar. Texans see themselves as a distillation of the best qualities of America: friendly, confident, hardworking, patriotic, neurosis-free. Outsiders see us as the nation’s id, a place where rambunctious and disavowed impulses run wild. Texans, it is thought, mindlessly celebrate individualism, and view government as a kind of kryptonite that weakens the entrepreneurial muscles. We’re reputed to be braggarts; careless with money and our personal lives; a little gullible, but dangerous if crossed; insecure, but obsessed with power and prestige.

Texans, however, are hardly monolithic. The state is as politically divided as the rest of the nation. One can drive across it and be in two different states at the same time: FM Texas and AM Texas. FM Texas is the silky voice of city dwellers, the kingdom of NPR. It is progressive, blue, reasonable, secular, and smug—almost like California. AM Texas speaks to the suburbs and the rural areas: Trumpland. It’s endless bluster and endless ads. Paranoia and piety are the main items on the menu.

Texas has been growing at a stupefying rate for decades. The only state with more residents is California, and the number of Texans is projected to double by 2050, to 54.4 million, almost as many people as in California and New York combined. Three Texas cities—Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio—are already among the top ten most populous in the country. The eleventh largest is Austin, the capital, where I live. For the past five years, it has been one of the fastest-growing large cities in America; it now has nearly a million people, dwarfing the college town I fell in love with almost forty years ago. Because Texas represents so much of modern America—the South, the West, the plains, the border, the Latino community, the divide between rural areas and cities—what happens here tends to disproportionately affect the rest of the nation. Illinois and New Jersey may be more corrupt, and Kansas and Louisiana more out of whack, but they don’t bear the responsibility of being the future.

I’ve always had a fascination with Texas’s outsized politics. In 2000, I wrote a play that was set in the state’s House of Representatives. The protagonist, Sonny Lamb, was a rancher from West Texas who represented House District 74, which, in real life, stretches across thirty-seven thousand square miles. (That’s larger than Indiana.) While I was doing research for the play, I met in Austin with Pete Laney, a Democrat and a cotton farmer from Hale County, who, at the time, was the speaker of the House. Laney was known as a scrupulously fair and honest leader who inspired a bipartisan spirit among the members. The grateful representatives called him Dicknose.

We sat down in the Speaker’s office, at the capitol. I explained that I was having a plot problem: my hero had introduced an ethics-reform bill, which triggered a war with the biggest lobbyist in the state. How could the lobbyist retaliate? Laney rubbed his hands together. “Well, you could put a toxic-waste dump in Sonny’s district,” he observed. “That would mess him up, right and left.”

Laney’s suggestion was inspired by an actual law that the Texas House of Representatives had passed in 1991. It allowed sewage sludge from New York City to be shipped, by train, to a little desert town in District 74, Sierra Blanca, which is eighty miles southeast of El Paso. The train became known as the Poo-Poo Choo-Choo.

“Another thing,” I said. “I’d like my lobbyist to take some legislators on a hunting trip. What would they likely be hunting?”

“Pigs,” Laney said.

“Pigs?”

“Wild pigs—they’re taking over the whole state!” Laney said. Feral pigs are a remnant of the Spanish colonization, and now we’ve got as many as three million of them, tearing up fences and pastureland and mowing down crops, even eating the seed corn out of the ground before it sprouts. They can run twenty-five miles per hour. “You ever seen one?” Laney went on. “Huge. They got these tusks out to here.”

“How do you hunt them?”

“Well, I don’t hunt ’em myself, but I got a friend who does.” He punched an intercom button on his phone. “Honey, get Sharp on the line,” he said.

In a moment, John Sharp was on the loudspeaker. The former state comptroller of public accounts, he is now the chancellor of the Texas A. & M. system. “Sharp,” Laney said, “I got a young man here wants to know how you hunt pigs.”

“Oh!” Sharp cried. “Well, we do it at night, with pistols. Everybody wearing cutoffs and tennis shoes. We’ll set the dogs loose, and when they start baying we come running. Now, the dogs will go after the pig’s nuts, so the pig will back up against a tree to protect himself. So then you just take your pistol and pop him in the eye.”

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/07/10/americas-future-is-texas