Can We Truly Talk About Fictional Characters?

Can We Truly Talk About Fictional Characters?

Several influential philosophers in the field of semantics have posited that sentences whose subject refers to some non-existent object in the spatiotemporal world are non truth-evaluable. Thus, we cannot talk about the number seven, ideas, and, most importantly, fictional objects. Since fictional characters are not included in the ontology of physical objects we cannot even say things that seem to be trivially true about fictional characters, such as "Holden Caulfield is a boy." We want to say true things about fictional characters, but can theories in the philosophy of language accommodate this want in a satisfying way?

In her Fiction and Metaphysics, Amie L Thomasson posits that fictional objects are "characters who appear in works of literature and whose fortunes we follow in reading those works". In her definition, the term "character" is not limited to human beings in fiction, but rather includes fictional animals, inanimate objects, events, and processes as well. Perhaps it would be better to use a term broader than "fictional characters" such as "fictional entities" that connotes a more inclusive set of fictional objects. So from here on, when I refer to "fictional characters" I am referring to all "fictional entities".

Thomasson's Artifact Theory

In the Artifact Theory, fictional characters are viewed as cultural artifacts. Central to the conception of fictional entities is the author's creative process--fictional objects were not discovered by the author in some abstract realm, but rather were formed by the author. Furthermore, a fictional character needs to hold ties to its origin. That is, if two fictional characters are remarkably similar in terms of their characteristics, they are only one and the same fictional character if they originate from the same source. The carry-over of characters from one book to that same book's sequel is an example of a common origin. To recap: in order for a fictional character to be brought into existence, it must be formed by its author.

The existence of a fictional character is sustained through literary works which may survive its author. For instance, if we want to talk meaningfully about Holden Caulfield, we can do so as long as at least one copy of The Catcher in the Rye exists. This raises an interesting question: once a literary work is created, does it always exist, or can it cease to exist?

I, as well as Thomasson, believe that literary works can cease to exist if all copies of the work are destroyed. This does not exclude the possibility of lost works, however. If it appears as if a certain work is destroyed and lost forever, but then suddenly happens to reappear, the work has always existed. However, if a work appears to be completely lost or destroyed, yet, contrary to the knowledge of the population, there exists a copy of the book buried somewhere in the world, the work is to be considered non-existent until rediscovered. Thus, a literary work is in existence so long as it is known to be in existence. Furthermore, the sustenance of a literary work depends on the language capacity of the human population. If a copy of The Catcher in the Rye is in circulation but no one on the planet is familiar with the English language, nor has any accessible means to become familiar, then the fictional objects in the book would be non-existent.

Philosophical Implications

Up to this point, I have described how fictional characters come into being as well as how they can cease to exist. One might ask how it is possible to refer to fictional characters as objects since referring terms in most dominant semantic theories are sufficient only if they refer to actual physical objects in the world. For a sentence such as "Holden Caulfield is a boy," Gottlob Frege, for example, would say that the sentence fails to refer, so therefore it is neither true nor false. The question of its truth simply does not arise.

Meinong theorized that there are certain objects which exist neither spatiotemporally nor non-spatiotemporally. These objects, he suggested, do not exist in any physical way, or any way at all. However, they do hold various properties. Such objects are referred to as Meinongian objects in the philosophy of language. Fictional objects are sometimes considered in a Meinongian light such that characters are non-existent spatiotemporally, however their essence is comprised of the various descriptions given in the text in which they appear.

However, conceptualizing fictional characters in Meinongian terms is problematic. We cannot refer to Holden Caulfield through a series of descriptions, such as "The 15-year-old boy that walks around wearing a red hunting hat and flunks out of school and..." since thousands of individuals could meet all of the (endless) descriptions that we give yet still differ from one another in significant ways. This is a problem because referring terms are supposed to identify one specific individual or object. In order for fictional objects to cohesively mesh with dominant semantic theories (such as Frege's) the issue of reference needs to be addressed. For instance, some sort of non-spatiotemporal ontological status needs to be ascribed to fictional objects that buy-and-large satisfies the semantic theorist.

Baptismal Theory

Saul Kripke's baptismal theory of reference in his Naming and Necessity may offer help. Kripke theorizes that when we refer to individuals--Barack Obama for instance--we refer to the name given to the individual Barack Obama during an original baptismal ceremony. In other words, the object Barack Obama was originally named Barack Obama by his parents shortly after he was born. We can talk about Barack Obama because this name that was donned upon him during the baptismal ceremony has been "passed from link to link" or person to person over time. When one individual first learns of the name 'Barack Obama' as referring to the person who is Barack Obama from a friend, the listener learns to associate the name 'Barack Obama' with the same person as the friend from whom he heard it. The friend who the listener learned Barack Obama from also learned Barack Obama from someone else in a similar way. Thus, when we speak of Barack Obama we all refer to the same individual as Barack Obama's parents did when they donned him 'Barack Obama.' Kripke believes that all proper names can be traced back to some baptismal ceremony, and that when we use proper names we always refer back to the baptismal ceremony through a chain of reference.

Kripke's baptismal theory of reference can be applied to fictional objects. In order to do so, we must give up the idea that it is necessary for fictional objects to refer to some actual person or thing. For instance, we must give up the idea that "Holden Caulfield" must refer to some actual person in the world named Holden Caulfield. Instead, we must be willing to accept the idea that "Holden Caulfield" could refer to an abstract artifact. The baptismal ceremony for a fictional character, such as Holden Caulfield, does not take place in an identical sense as it does with a human such as Barack Obama. Rather, it occurs through the physical text of the novel in which the character is contained. Characters are baptized when the author names them in his/her story. Thus, the baptismal ceremony for Holden Caulfield occurred when J.D. Salinger named the main character in his book Holden Caulfield. Moreover, Salinger baptizes Holden Caulfield when he links the name 'Holden Caulfield' to the descriptions of his main character. Chains of reference for fictional characters are maintained in a similar fashion as chains of reference for physical objects. As aforementioned, the reference chain to Barack Obama would lead back to the baptismal ceremony, and this chain would be spread via word of mouth, news stories, etc. The chain of reference for fictional characters, on the other hand, is primarily known through the many copies of the text in circulation. There are millions of copies of The Catcher in the Rye around the world, and this is the primary means in which individuals become acquainted with the character Holden Caulfield. It does not matter which copy of the book one has, the chain of reference will always lead back to the baptismal ceremony performed by the author.

I Object!

One may object that, under the baptismal theory of reference, fictional characters are incomplete entities because certain facts about their person are not described within the text. For instance, one may ask at what age was Holden Caulfield when he first learned to talk. Consider the sentence "Holden Caulfield learned to talk at age two." If we can refer to Holden Caulfield, he must have learned to talk at some age. Therefore, such an attribute should be able to be attributed to his person. If not, it seems as if his character is incomplete.

In order to address this objection, we need to consider what Thomasson describes as the fictional context. The fictional context, as opposed to the real context, implicitly prefaces every sentence regarding a fictional character with "according to the story." This allows us to realize that we are not talking about a real, physical realm when we discuss Holden Caulfield, but rather the realm of the fictional abstract. Under such a formulation, the sentence the objector presents above would be read "According to the story, Holden Caulfield learned to talk at age two." This sentence would be neither true nor false under Mengionian logic since the attribute of when Holden Caulfield first learned to talk does not arise within the text of the story.

Does This Fiction Theory Vibe With Semantics?

In his famous Sense and Reference, Gottlob Frege lays out a foundational semantic account for objects which is divided into sense (sinn) and reference (bedeutung). Consider the following two sentences:

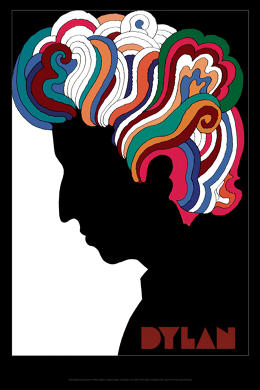

A: Bob Dylan was born in Hibbing, Minnesota.

B: Robert Zimmerman wrote the song "Like a Rolling Stone."

To Frege, the sentence-subject in both A and B have the same reference, but different senses. Robert Zimmerman and Bob Dylan both pick out the same object in the world, which means that they both have the same referent. On the other hand, the sentence-subject in both A and B have different senses. "Bob Dylan" and "Robert Zimmerman" are both different modes of presentation for the object that they pick out, and thus they have different connotations. To illustrate sense, consider someone who knows who Bob Dylan is and some famous songs that he wrote. Furthermore, assume this someone does not know that Robert Zimmerman is the same person as Bob Dylan. If this someone was presented with B, she might think that it's false. However, if "Bob Dylan" were substituted for "Robert Zimmerman" in B she would affirm it as true. Although in reality both statements would have the same referent and both would be true, the sense of the subject changes how the sentence is evaluated in certain instances.

For sentences, Frege states the sense is a function while the referent is an input in that function which points to a truth value. For instance, the predicate "____is a boy" would be a sense of a sentence, however, the sentence is incomplete without a referring term placed in the argument slot. If we were to input "witty" into the argument slot, the sentence would come out true since I am in fact an object in the spatiotemporal world and I happen to be a boy. For fictional objects, on the other hand, Frege's account does not yield satisfying results as it stands. If we were to input "Holden Caulfield" into the argument slot instead of "witty" the sentence function would spit out neither a true nor a false truth value. Since "Holden Caulfield" does not refer to anything in the spatiotemporal world, the sentence "Holden Caulfield is a boy" has a non-referring argument slot and is thus an incomplete sentence. It would be the same as if the predicate "___is a boy" was standing alone.

To me, this is problematic given certain contexts that the sentence could appear in. Consider a book club sitting in a circle discussing The Catcher in the Rye. If someone says "Holden Caulfield is a troubled young man who needs direction." Another member of the book club is not going to stand up and exclaim "Holden Caulfield does not exist!" It is understood in such a fictional context that the speaker is not referring to the real actual world, but an abstract fictional realm created by J.D. Salinger in which Holden Caulfield is a troubled young man who needs direction. Such a context will be called a fictional context. Conversely, if a friend approached you today and said "I saw Holden Caulfield today and he looks like he's troubled and needs direction." In such a real context, one could rightfully respond by claiming that "Holden Caulfield does not exist." The utterer of the original sentence claimed to have physically viewed a fictional character, which implies that he's not speaking about a fictional realm and therefore not within a fictional context. He is thus engaging in what is known as the real context, which operates under the supposition that the subjects of your sentences actually exist. In the real context, claiming to have seen a fictional character is ludicrous.

In Frege's theory, if the context of statements are acknowledged, we can talk about fictional characters in a meaningful way. The reference of "Holden Caulfield" is determined by the fictional artifact theory combined with Kripke's baptismal theory. In a fictional context, when we make an utterance such as "Holden Caulfield is a boy" we know that "Holden Caulfield" refers to the character that J.D. Salinger baptized as "Holden Caulfield" in his book The Catcher in the Rye. And in this story, we know that Holden Caulfield is in fact a boy so we therefore know that when the sense "Holden Caulfield" is inserted into the predicate "___is a boy," it is in fact true.

Let me know your guys thoughts on fiction and reference. I'm interested to listen.

Also let me know your thoughts on the more formal post style. This is easily my most structured to date and I'm looking for feedback :)

Congratulations @witty! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about this award, click here

There are many fictional accounts, I meant people... round here.

Thanks for your good posts, I followed you! +UP

Congratulations @witty! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Congratulations @witty! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!