Do the ends justify the means in conducting research with children?

Thoughts on the child participant and the ethics of child research

Photo taken from Kitchen Makeover

Prior to the Refrigerator Safety Act (RSA) passed in 1956, refrigerators were unable to be opened from the inside. This was not an issue unless you were a small child looking for the next best hide-and-seek spot. Refrigerators built prior to the RSA could not be opened from the inside, becoming death traps by suffocation for many unsuspecting children. According to this source, the New York Times reported that 115 children had died in this way between 1946–1956.

The development and passing of the RSA was largely owed to a study conducted by Bain et al. in 1958, in which child participants were seperated from their caretakers and lured them into one of various entrapment simulators, in order to find out what would be most effective in helping them escape. Their study and the subsequent passing of the RSA have been correlated with a 75% decrease in deaths from suffocation in a refrigerator over the next 20 years. However, it would be incredulous to conceive of such a study being conducted today given our current ethical standards.

Photo of device used in Milgrim’s study taken from PsychBlog

Many vital conclusions, with implications for our understanding of the world or for the benefit of humankind, have been drawn from studies which inflicted great harm or risk upon its participants, especially in the realm of psychology. Several that immediately come to mind are the Tuskegee syphilis study, Milgrim’s Behavioural Study of Obedience and Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment. However, it would be unthinkable for such studies to withstand public scrutiny today, let alone pass through the various institutional review boards and rightly established research ethics guidelines.

I believe today’s ethical standards, with more weight placed on the means than the ends, have been rightfully established. The ends do not justify the means in conducting research — especially with children. The Belmont report distilled three ethical principles to be considered when doing research involving human subjects: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. These principles are at the foundation of the guidelines researchers adhere to today, and I will discuss how they are operationalized to illustrate why the means do not justify the ends for child research.

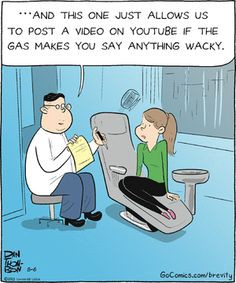

Image taken from picofunny

The first principle — respect for persons, is manifested primarily in voluntary and informed consent. It’s acceptable for experiments with minor harm or risk to normally functioning adult participants to be carried out with their voluntary and informed consent with the knowledge they are participating for the good of others. However, children are not capable of consenting in the same capacity, and are not in a position to take on any harm or risk. Piaget’s questioning of children about punishment demonstrates children having a different understanding of morality, and incapable of understanding what they would be consenting to and its implications; at least in the same capacity as an adult. This inability to understand complicates compliance and debriefing as well. Parents should not be able to give consent on behalf of their child, the same way a boss should not be able to give consent on behalf of their subordinates. Soothing or persuading children to participate is also deceptive in a manner that should not be justified by a child’s lack of understanding.

Image taken from Funny Dental Cartoons

Beneficence, the second principle, is operationalized by minimizing harm and doing good, while justice, the third, by fairly distributing risks and benefits. Participants should benefit from being part of a study. Research tends to focus on minimizing harm for participants, and doing good for others through the conclusions of the study. While the Milgram and Zimbardo experiments are cases which illustrate this in the extreme, it is inevitable that research will benefit those in the future more, as they will usually take on less risk and harm than participants. Regardless, researchers need to ensure that participants are not exposed to risk or harmed while the benefits are distributed elsewhere, especially for children, who are less able to perceive this cost-benefit ratio and distribution.

To give credit to Bain et al.’s refrigerator study, the researchers did include a follow-up study 8 months later, in which they interviewed the mothers’ of the child participants to see if they were traumatized in any way. This follow-up also yielded interesting insights, such as how adverse reactions to a situation might be caused by children picking up cues of distress from their caretakers. The absence of caretakers in the study could explain why children participants were largely unaffected by the experience, and inform our understanding of how trauma might develop for children.

Image taken from Cartoon Stock

On the other hand, without digressing further, it seems that safer fridges could have been constructed without needing to subject any children to risk or harm. Alternatively, the study could have been conducted with less ecological validity in place of an education element, while still extracting the necessary information to remodel refrigerators.

We are over-protective of children today, to the point where we might be less beneficent towards them by withholding opportunities for them to grow. Studies can be beneficial and help child participants develop traits like self-efficacy, while simultaneously advancing our understanding of child psychology. Children are resilient and our influences on them might be less permanent, or have the opposite effect than we might think — their anxiety might simply reflect their parents. However, while we should not err too heavily on the side of caution in setting overly restrictive ethical guidelines, I believe the child participant’s welfare should be what researchers primarily focus on, even if we have to sacrifice potential findings that could be made in absence of these guidelines. How could Bain et al.’s study have been conducted in a way that would benefit child participants?

Photo taken from LowBoredom

Please let me know if you would be interested in publishing in PsychBites, a growing collection of writings on topics in psychology. This article is also posted on Medium and LinkedIn.

Congratulations @jerald! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPi upvoted your post plz upvote me back !!

Thanks and upvoted!

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://medium.com/psych-bites/do-the-ends-justify-the-means-in-conducting-research-with-children-c24a9d8e1c1

Hi. I am a volunteer bot for @resteembot that upvoted you.

Your post was chosen at random, as part of the advertisment campaign for @resteembot.

@resteembot is meant to help minnows get noticed by re-steeming their posts

To use the bot, one must follow it for at least 3 hours, and then make a transaction where the memo is the url of the post.

If you want to learn more - read the introduction post of @resteembot.

If you want help spread the word - read the advertisment program post.

Steem ON!