Smart Cities and Surveillance: Descriptive Foundation & Belgian Regulatory Framework

Surveillance schemes are justified “on the basis of arguments accompanied by rhetorics of security which are likewise endorsed by private companies” (Galetta, 2013: 229). Such technologies are implemented without involving the public while the government is promoting surveillance technologies like CCTV as a crime prevention measure.

“In 2012 the Belgian Ministry of the Interior encouraged businessmen and professionals to implement new CCTV systems in exchange for fiscal advantages and benefits” (Galetta, 2013: 221).

One of these recent developments, together with the political promotion, are IP camera systems. They form a digitized version of CCTV distributing its content over networks. The benefits of traditional analog surveillance cameras range from a user- friendly character and improved search capability to content compression for facilitated storage in any geographic location. Also, remote control is possible since anyone inside the network can potentially use the footage. This facilitates immediate distribution and thus leads to a growing industry providing these standards.

Apart from research and innovation, the development of technologies depends on supply stimulation from consumers. Therefore, latent interests in a complex system of involved stakeholders are likely to steer demand in certain favorable directions. Hence, it does not come as a surprise that organizations emerged, pushing towards standardization and interoperability of surveillance devices regardless of their manufacturer. But, the standardization comes with a loss of quality as well as additional features, which renders standards that are useless to open-street CCTV systems while businesses prevalently use it.

The justification of increasing surveillance devices is accompanied by rhetorics of security. This resembles the Thomas theorem that stipulates the following: “if men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas, 1928: 572). Therefore, a ubiquitous, even though potentially irrational, collective fear is sufficient to implement surveillance systems as the solution to those emotions. Nowadays, when talking about security, the notion of terrorism is usually not far fetched and used to justify the implementation of surveillance technology. In response to such threats, governmental efforts aiming at prevention have increased because this is a factor that interferes with public safety. The potential negative impacts on civil liberties and privacy, as well as the adequacy of protection, are elaborated throughout this work. In regards to the Thomas theorem, Beck (1992) proceeds in a similar direction when talking about the contextualization of threats through articulation.

“The immediacy of personally and socially experienced misery contrasts today with the intangibility of threats from civilization, which only come to consciousness in scientized thought, and cannot be directly related to primary experience” (Beck, 1992: 52).

The implementation and proliferation of surveillance technology are the results of a complex interaction of specific factors whereas uniform trends are hardly identifiable. This interaction can be related to social, demographic or economic factors; political configurations based on internal dynamics of power or historical events; the result of crises, particular events or moments in which politicians feel pressured into taking action; or national politics and local media as drivers for the deployment of surveillance camera systems in general (De Schepper & De Hert, 2013: 147). Even though camera systems are implemented on a municipal level, “the federal government still is competent for some trans-regional policy matters, of which public safety (Ministry of Internal Affairs), justice (Ministry of Justice) and privacy (Belgian Data Protection Authority, which is related to the Ministry of Justice) are important”. As of 1992, Belgium has known a judicial regulation regarding privacy and social control through surveillance technology when:

“a national Privacy Act was voted in the Belgian Federal Parliament, containing a general framework for privacy principles. In 2007, the Belgian Federal Parliament voted a national Camera Act, which added specific rules for the use of public and private use of CCTV. After this Act was adapted by parliament in 2009, the Belgian Minister of Internal Affairs declared in parliament that this Act also regulates the use of ANPR cameras“ (De Schepper & De Hert, 2013: 148).

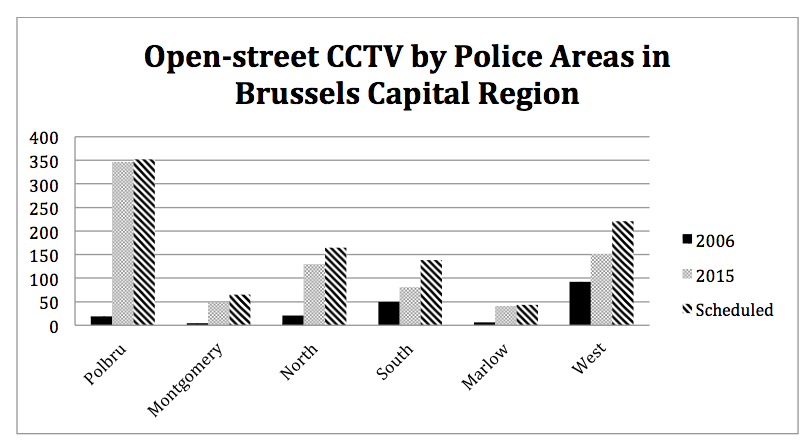

The following figure (Fig. 1) shows the proliferation of surveillance devices in the Brussels-Capital Region. However, this is a simultaneously increasing development throughout Belgian urban areas with a high population density (De

Schepper & De Hert, 2013: 158). CCTV placements in Brussels have been fostered throughout the “Camera Plan 2010-2012” with a total budget of “8 million Euros” (City of Brussels, 2009) under the cloak of public safety while protecting privacy.

Fig. 1: Open-street CCTV by Police Areas in Brussels-Capital Region (De Keersmaecker & Debailleul, 2016)

Polbru contains the districts Ixelles, Brussels City, Laeken, Neder-Over-Hembeek and Haren. Montgomery includes Etterbeek, Woluwe-St. Pierre, Woluwe-St. Lambert. North is St. Josse, Schaerbeek, Evere. South contains Anderlecht, Forest, St. Gilles. Marlow includes Uccle, Watermael-Boitsfort, Auderghem. West is Molenbeek, Koekelberg, Ganshoren, Jette, Berchem.

The total amount of open-street CCTV in the Brussels-Capital Region rose from 192 in the year 2006 to 796 in 2015 and will go as high as 984 with the scheduled cameras for the near future. The number of ANPR devices in the Brussels- Capital Region in 2015 was 378 in total with 30 outdoor cameras and 348 in tunnels. Even though municipalities initiated these surveillance schemes, the control of those public cameras shifts gradually towards police areas (De Keersmaecker & Debailleul, 2016: 2-4).

Apart from camera systems, the concept of ‘nodal orientation’ or ‘infrastructure policing’ refers to the surveillance of infrastructures such as mobility, goods, money, and information. It is used for the control of transnational transits as an effective tool for cross-bordered criminality by local police forces because it offers a collection of yet unconnected projects of surveillance of regional municipalities (De Schepper & De Hert, 2013: 148). In a similar vein, Johan de Becker, commanding officer of Brussels-West Police Zone, announced in an interview that a CCTV-sharing project contributes to urban management (Brussels Smart City, 2016). The structural solution to budgetary restraints and decreasing police capacity, which was limited by the Belgian Ministry of Internal Affairs in 2007, are CCTV systems fulfilling basic police services while being less expensive (De Schepper & De Hert, 2013: 159). According to the four-stage diffusion theory, the development of CCTV evolves from private sectors with relatively unsophisticated systems in the first stage to key institutional areas of public infrastructure in the second. The third stage is marked by limited diffusion in the public space and varying organizational authorities. During the final fourth stage, CCTV and surveillance are omnipresent in the form of blanket coverage and large-scale system integration like ANPR (Norris, McCahill & Wood, 2004: 119-20).

In Belgium, the implementation of technology developments like ANPR outpaces certain regulatory solutions and has compromised the rule of law due to a lack of judicial accountability. For instance, the freedom of movement or the presumption of innocence is bypassed by the automatic capture of drivers’ details by ANPR (Ball et al., 2014: 30), which is „against the principle of foreseeability (Art. 8.2 of the European Convention on Human Rights)“ (Galetta, 2013: 232). The main regulation in Belgium’s, both emergent and outdated, legal framework is the ‘Loi Caméras’ and its 2009 amendment, which clarified some key aspects; yet ambiguities about the legality and usage do exist. It applies to “any fixed or movable system of observation whose aim is to prevent, ascertain or detect crimes against persons or assets or offences [sic] of the same kind (Art. 2, 4)“ (Ball et al., 2014: 54). The Loi Caméras provides specific regulation and clearer provisions for CCTV, though it is unclear if it applies to ANPR in a general context, as those cameras are related to a different technology. The Privacy Commission admitting the use of mobile cameras by the police in the case of large crowd gatherings addressed the ambiguity in 2012. This adaptation also gave legal coherency to fixed ANPR cameras and a new amendment by the Belgian Senate in 2014 embodied the legitimate use of mobile ANPR in the law (Ball et al., 2014: 53-5). Yet, the rules and strategies regarding the implementation and installation of ANPR cameras by federal police forces and public authorities do not ask for any evaluation of accountability mechanisms (Ball et al., 2014: 70). Among the factors contributing to the complexity of involved factors are the low public awareness, a lack of political debate and the resilient assessment of impacts on privacy. Although this has begun to change recently, the media coverage on surveillance predominantly emphasizes the added value instead of the potential repercussions regarding fundamental rights and freedoms (Ball et al., 2014: 7).

References

Ball, K., Dahm S., Friedewald, M., Galletta, A., Goos, K., Jones, R., Lastic, E., Norris, C., Raab, C. & Spiller, K. (2014). Chapter Two – Automatic Number Plate Recognition. IRISS – Increasing Resilience in Surveillance Societies, 25- 77

Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society – Towards a new Modernity. London: Sage Publications

Brussels Smart City (2016). “By definition, sharing CCTV is a smart-city approach”. Retrieved 23.11.2016, from smartcity.brussels/news-113--by-definition- sharing-cctv-is-a-smart-city-approach

City of Brussels (2009). Municipal news 2009. Retrieved 10.11. 2016, from www.brussels.be/artdet.cfm?id=5601&highlight=camera

De Keersmaecker, P. & Debailleul, C. (2016). The spatial distribution of open-street CCTV in the Brussels-Capital Region. Brussels Studies, 104, 1-16

De Schepper, T. & De Hert, P. (2013). A Descriptive Review of the Use of CCTV in Flemish Municipalities. In W. R. Webster, G. Galdon, N. Zurawski, K. Boersma, B. Sagvari, C. Backman, & C. Leleux (Eds.), Living In Surveillance Societies: The State of Surveillance, 145-161. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

Galetta, A. (2013). IRISS WP3 – Case Studies – ANPR in Belgium. IRISS – Increasing Resilience in Surveillance Societies, 213-238

Norris, C., McCahill, M. & Wood, D. (2004). The Growth of CCTV: a global perspective on the international diffusion of video surveillance in publicly accessible space. Surveillance & Society, 2(2/3), 110-135

Thomas, W. I. (1928). The Methodology of Behavior Study. In Thomas, W. I. & Thomas, D. S. (Eds.), The Child in America: Behavior Problems and Programs. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 553-576. Retrieved 07.04.17, from brocku.ca/MeadProject/Thomas/Thomas_1928_13.html