Seeking Humanity in a Prison Passion Play

Seeking Humanity in a Prison Passion Play

Image

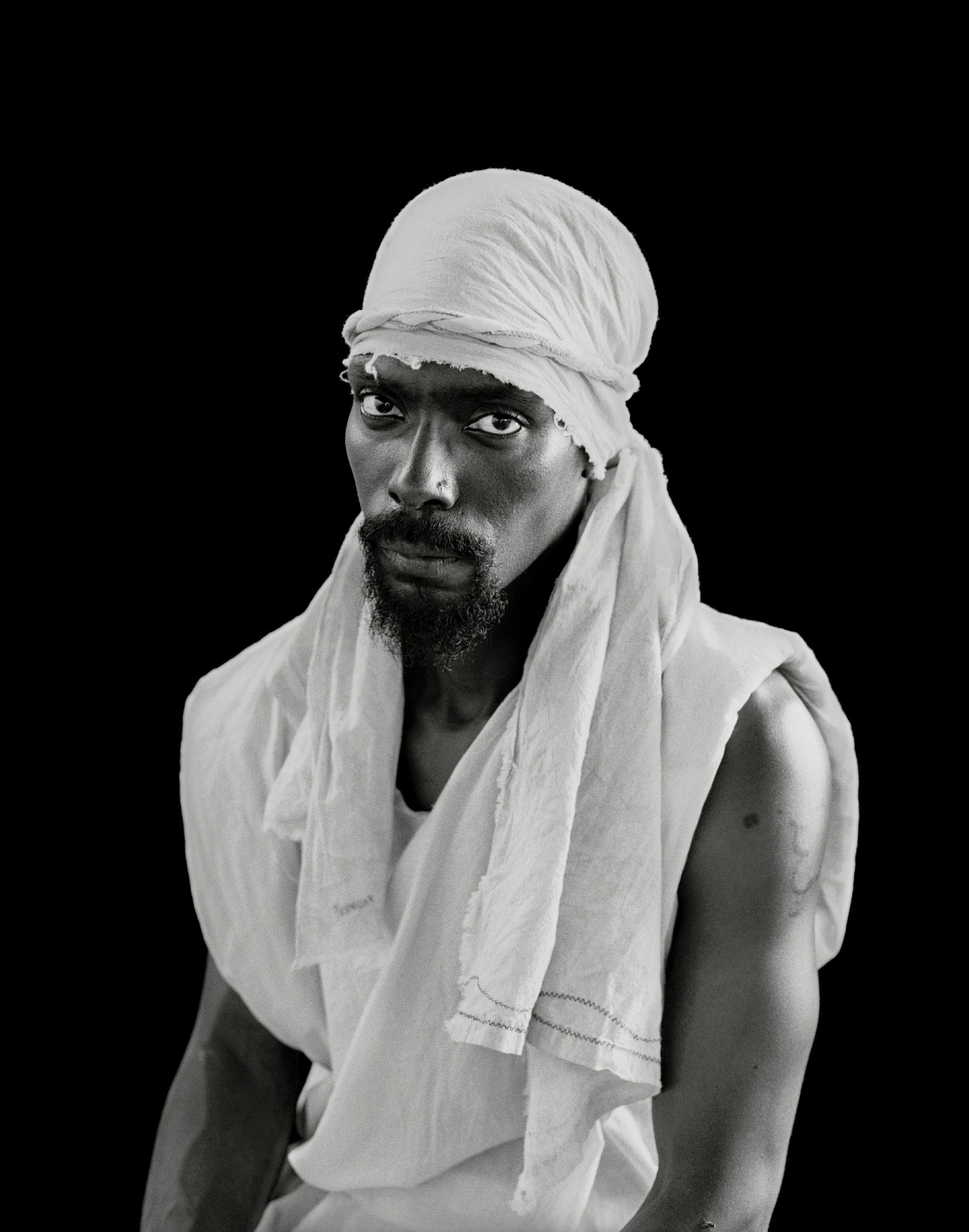

Levelle “Black” Tolliver as Judas in a play, at Angola prison, about the life and death of Jesus Christ.CreditDeborah Luster, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

By Andrew Boryga

Feb. 6, 2018

There are more than two million incarcerated people in the United States. We, the public, have seen countless images of them: Arms laced between rusted metal bars; gloomy faces staring at us, backs against a white wall; bodies shrouded in orange jumpsuits. These images pop up over and over in our cultural lexicon, but do little to make us consider the individuals portrayed.

“When we think of the word mass incarceration we think of the word mass,” said Nicole Fleetwood, an associate professor of American studies at Rutgers University and scholar on incarceration. “But every person has a story.”

Ms. Fleetwood has now collaborated with Aperture magazine on its latest issue, “Prison Nation,” which features the work of more than a dozen photographers and writers. The issue addresses the role photography can play in creating a visual record of mass incarceration that focuses less on prisons and more on the human beings inside.

Image

Bobby Wallace as Jesus Christ in the prison play.CreditDeborah Luster, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

“A lot of the images we see related to incarceration are destructive,” said Michael Famighetti, Aperture’s editor. “We looked for projects that highlight individuality within the system from different points of view.”

Ms. Fleetwood and Mr. Famighetti said the prospect of giving inmates the power to decide how they appear and how to showcase their humanity was central to “Prison Nation.” Often that power is used against inmates, but with the release of the issue and the lineup of public lectures and presentations in New York and other cities across the country that will follow, they hope to change that.

The featured work includes Bruce Jackson’s photos of Southern prisons in the 1960s and ’70s that eerily resemble plantation life; Jack Lueders-Booth’s intimate portraits of female prisoners four decades ago posing as they wanted to be seen, with no barbed wire or uniforms; and Lucas Foglia’s more recent, buoyant images of inmates at Rikers Island tending gardens. Essays include a meditation on the history of the mug shot by the scholar Shawn Michelle Smith and a conversation between the photographers Jamel Shabazz and Lorenzo Steele, Jr., who both previously worked as corrections officers on Rikers Island.

Some of the most striking photographs are Deborah Luster’s portraits of inmates acting in a production of “The Life of Jesus Christ” at Angola prison, the notorious maximum security prison in Louisiana. The play was staged three times between 2012 and 2013 before an audience of inmates, family and the public.

Image

Jamal Johnson as a Roman soldier.CreditDeborah Luster, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

Image

Mary Bell as Anna.CreditDeborah Luster, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

Ms. Luster’s photos are stark. The background of each seated actor is clouded in black. Their gaze is a cocktail of serious brooding and reflection, each channeling his or her inner Brando. Their costumes were made by their own hands: to portray a Roman soldier, a breastplate was fashioned from scavenged vinyl, a football helmet was reconfigured to resemble that of a warrior, and swords were made from cardboard and duct tape.

Ms. Luster said the performance was held in the prison’s famed rodeo arena, where she made each portrait backstage, under the bleachers. At one point, a camel was in the next stall.

However comical the conditions were at times, none of this is visible in her photographs. Ms. Luster said the inmates changed dramatically after putting on their costumes, completely inhabiting their characters. She was not surprised. After all, prison is the ultimate theater. “You have to be one person to the guard, you have to be another person if someone is threatening you,” she said. “There are all these characters. If you are going to survive in that environment you have to be an actor.”

Image

Earl “Trinidad” Davis as John the Baptist.CreditDeborah Luster, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

Image

James Blackburn as Roman horse soldier.CreditDeborah Luster, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

Discussing the profound change in demeanor she witnessed, Ms. Luster remembers one inmate in particular: Vernon Washington, whose nickname was Vicious. He was a champion boxer, and like the other 70 inmates in the play, serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. By the end of one performance, which is about redemption, Ms. Luster recalled another inmate referring to Vernon by his nickname. He replied, “I don’t want to be called Vicious anymore.”

If you are like me, you might be curious why Ms. Luster did not go for more dynamic scenes on stage. However, she said that after collaborating with the poet C. D. Wright on “One Big Self,” a book culled from 25,000 portraits of Louisiana prisoners she photographed between 1998 and 2002, she began favoring the still, direct approach. If anything, the people she photographed weren’t posing for her; they posed for their mothers, girlfriends, husbands, fathers and children they would send her pictures to.

“They were not giving themselves to me,” she said, “they were giving themselves to people that they loved.”

Image

Vernon “Vicious” Washington as Pharisee.CreditDeborah Luster, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Galler