The Parable of the Two Clocks

A Short Story : A Tall Tale

My father was a merchant of Lindalino : I was his only son. When I was a boy of seven or eight, and still accustomed to wearing short breeches, he offered to take me with him on one of his many voyages to Laputa. I had heard so many tales of that fabulous land—some of them from my fathers own lips—that I could scarce believe my good fortune.

A week later we set sail in my fathers vessel, Perseverance, a stout ship of some three hundred tons. After a short sea passage we arrived at the famous isle, the sight of which took my breath away. The reader can hardly conceive my astonishment to behold an island in the air, inhabited by men, who were able (as it should seem) to raise or sink, or put it into progressive motion, as they pleased. A chain was let down with a seat fastened to the bottom, to which I and my father were fixed, and we were drawn up by pulleys.

My first impressions of Laputa overwhelmed me. I had never before laid eyes upon such a place. I could see that it was encompassed with several gradations of galleries, and with stairs at certain intervals to descend from one to the other. The buildings were of an immensity that beggared my belief, and were finely wrought of the most beautiful stones—marbles, granites, and many others that I could not put a name to. The rampier which enclosed it all about was twenty feet and a half high, and at least eleven feet broad, so that a coach and horses could be driven very safely round it, and it was flanked with strong towers at one hundred yards distance. In all my short life I had not seen a more populous place. The shops and markets were well provided, and the populace lived in the greatest plenty and magnificence, and were allowed to do whatever they pleased. I thought it the most delicious spot of ground in the world.

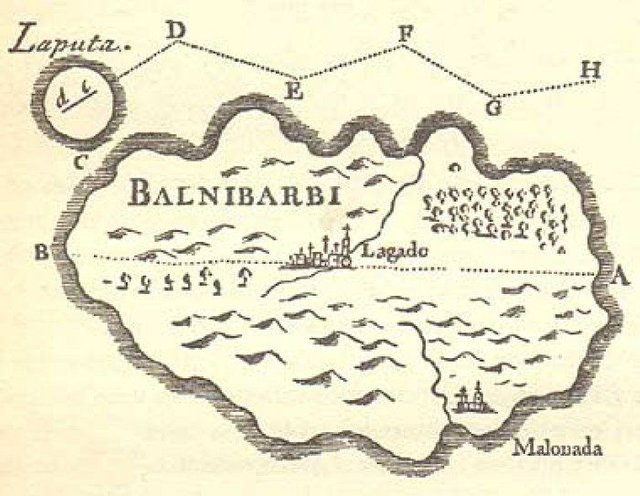

When my father had successfully transacted the business that had been the occasion for our visit, he took me to see the curiosities of the flying island. I remember looking over the rampier and seeing the metropolis of Lagado—as my father informed me—so far below me that I could not make out the streets, or even the public parks, notwithstanding one or two of the latter are of considerable extent. We visited also the Parliament of Laputa, where the Elders of the People are wont to conduct the affairs of state on behalf of his majesty the King of Balnibarbi. A debate was in course on some question of Laputan economics, but to judge from the number of delegates who wished to speak and the nicety of their arguments, we did not anticipate a speedy resolution. After a short interval, we accordingly withdrew.

We went next to view the royal palace, where the king holds court. For Laputa, as I learned, is merely the royal demesne of the Kingdom of Balnibarbi, which encompasses also a considerable extent of the mainland. I gaped to behold the stately edifices, the imposing monuments and the noble statuary that grace his majestys private residence. The palace stands in the midst of spacious gardens, in which all manner of flowering plants flourish and an abundance of small birds and animals have their habitations. The palace itself was not open to casual visitors, but we had the liberty of the royal gardens to stroll in at our pleasure.

I shall not trouble my reader with all the curiosities I observed, being studious of brevity, but pass instead to the most lasting impression I received that memorable day, an impression I owe to something quite different from imposing buildings or matters of state.

The time appointed for our return to Lindalino not yet being come, we repaired to the grand Academy, where the scholars of natural philosophy are wont to conduct their researches and prosecute their experiments. This academy is not an entire single building, but like the Kings residence, it comprises many edifices set apart from the rest of the island. It is surrounded by an estate of pleasant gardens and walkways and is compassed about by an enclosing wall. A member of the Academy, a doctor of natural philosophy as it chanced, was kind enough to show us the institutions principal points of interest, but I fear I should exhaust the readers patience were I to enumerate these.

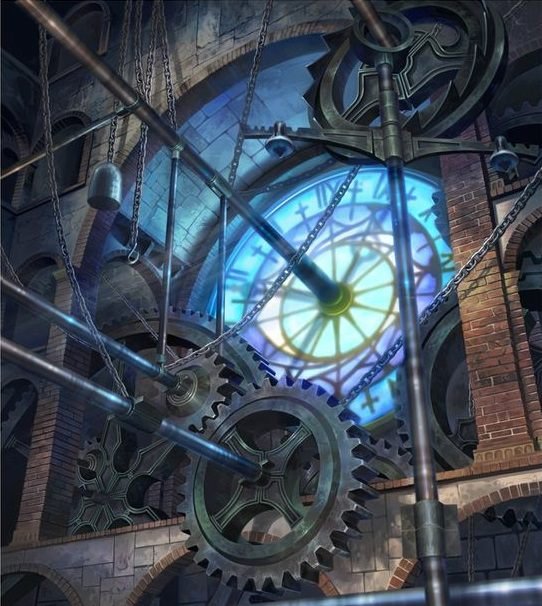

Our final port of call was the magnificent Hall of Sciences, where the natural philosophers of the Academy—by which I mean the astrologers, atomists, alchemists, engineers, natural historians, doctors of physic, mathematicians, etc.—present their newest findings, demonstrate their latest inventions, and debate matters of controversy. I cannot begin to describe the immensity of this huge space, which is of rectangular form, rather after the manner of a Roman basilica. In length it must exceed five hundred yards, so that the far wall is all but invisible to the visitor who enters on the opposite side. The width is of a size proportionate with the length. The four walls of the Hall are provided with niches in which the divers sciences are represented by statues of the founders or most celebrated practitioners of those sciences. Archimedes, for example, stands for the mathematicians, Kanada Kashyapa for the atomists, Ibn Sina for the doctors of physic, and Maria Skłodowska for the alchemists.

But my eyes did not tarry long among these eminent personages. Only a few minutes had elapsed since our arrival when our ears were greeted with the musical tintinnabulation of distant bells. Looking around, I soon realized that this sound was emanating from an instrument at the farther end of the Hall. I freely own myself to have been struck with inexpressible delight upon hearing these chimes. My father asked our guide what might be the source of this pleasant music.

— What! the man replied, overcome with astonishment. Are the inhabitants of Lindalino ignorant of the Great Keeper of Time? How is it that you have never heard of this wonderful device? Its fame reaches beyond the borders of Balnibarbi even to the ends of the known world.

— Ah, so that is the celebrated Keeper of Time? my father asked, pointing in the direction of the strange instrument at the other end of the Hall, from which the chimes had come. We citizens of Lindalino are not as ignorant of the outside world as you might think. Of course we have heard of the Great Keeper of Time, but this is the first time I have had the honor of standing in its presence and seeing it with my own eyes. I always pictured it as a sort of gargantuan hourglass, or a large sundial, perhaps. But this? This beggars the imagination.

As we walked towards the Great Keeper, our guide briefly recapitulated its history: how it had been constructed many centuries before by Chronos, a member of the Academy of Natural Philosophy, who was now held in legendary esteem : how it had never lost or gained in all those centuries so much as a single second when compared with the movements of the Sun and the stars : how Chronos had taken the secrets of its internal mechanism to his grave : and how no other member of the Academy had ever succeeded in replicating the Great Keeper of Time, notwithstanding many had tried.

As our guides tale drew to a close, we found ourselves at the foot of the Great Keeper. I had never before beheld any object that might be said to resemble it in either its size or its appearance. It stood perhaps two hundred feet tall, but in both its breadth and its depth it was no more than twenty feet across. You might, on first beholding it, compare it to a tower, or, perhaps, to an obelisk. Almost at the top of this structure, a large circular disk had been fitted into its façade. The outer circuit of this dial—as, I later learned, it is properly called—was inscribed in order with the first twelve numerals, twelve being in the superior position and six opposite it in the inferior. The circumference of the dial was divided by small strokes into sixty equal divisions. Attached to the dial were three spokes or radii of different lengths. Each spoke was fixed to the centre of the dial and was free to rotate about that centre.

It is by means of these hands, as they are called, that the Great Keeper tells the time. The longest hand tells the seconds, completing one rotation in sixty seconds: for this reason, it is known as the second hand. By the same reasoning, the hand of middling length is known as the minute hand: it tells the minutes, completing one rotation in sixty minutes. The shortest hand is the hour hand: it tells the hours, and completes each of its rotations in twelve hours. How the Great Keeper contrives to move each of these divers hands at the correct rate, keeping pace with the other two, so that all three remain perfectly synchronized with the risings and settings of the Sun, and with the equinoxes and solstices thereof, is still a mystery, for no one other than Chronos himself has ever seen the inside of the Keeper. The inner workings of this device are still as great a puzzle to us as the machinery of the human brain.

The chimes that had first attracted our notice to the Great Keeper announce the four quarters of every hour, each with its own distinctive jingle. Thereby it is possible for any man to estimate the time of day or night when he is within hearing of the Great Keeper, even if he cannot see it. This ingenious property is a great virtue, for I subsequently discovered that the chimes of the Keeper can be heard in all parts of Laputa, though one must repair to the Hall of Sciences if one wishes to read the precise time on the dial.

On that fateful day, as I stood in awe before the Great Keeper of Time, I made it my lifes ambition to build a keeper of time of my own—a chronometer, as we now call such devices, in honor of the legendary clockmaker. I do not mean some prodigy that people would come from the other side of the world to gape at, but a small device that could be set up in a mans house, or that he could carry about on his own person, and that would tell him the exact time of day whenever he had need of such knowledge. I could see at once the advantages of such a thing. I flattered myself to think that such an invention might even have a revolutionary effect upon society.

The time of our departure being come, we repaired without further delay to the lowest gallery of Laputa, where we were let down to my fathers ship by the same system of pulleys that had earlier raised us up. We set sail with the first favorable tide. The homeward voyage being without incident, I shall not test the readers patience with any account thereof.

On the very day we dropped anchor in Lindalino Bay, I threw myself with transport into my self-appointed task. My father came to regret that he had ever taken me to Laputa. It had always been his fervent hope that I would one day learn his trade and become a merchant in my own turn, that I would sail with him on the Perseverance while he was yet a young man, and support him in his old age when he was no longer fit to go to sea. But I instead spent the greater part of my time with my head buried in books, learning all that I could concerning the sciences of mechanics and chronometry, wherein I had a great facility by the strength of my memory. My hours of leisure I spent in reading the best authors, ancient and modern, being always provided with a good number of books. And whatever time I did not spend in reading, I devoted to the construction of mechanical devices and curios of divers species.

Notwithstanding his disappointment, my father continued to grant me a very scanty allowance. This I laid out in learning engineering and other parts of the natural philosophies useful to those who intend to devote their lives to the accomplishment of some great project, which I now believed it would be, some time or other, my fortune to do.

When, at the age of sixteen, I had completed my schooling—having by then obtained by dint of hard study a good degree of knowledge in all the branches of natural philosophy—I applied to continue my education at the Academy of Natural Philosophy on Laputa, and by the will of the gods I was accepted. My father, who had by now reconciled himself to my strange vocation, took me once again to the flying island and left me—with some regret, and many tears, but no little hope for my future—in the care of the learned doctors of philosophy.

A small but well-appointed apartment was provided for me in a pleasant part of the Academys campus, where I resided three years, and applied myself close to my studies. I studied astrology two years and seven months, knowing it would be useful to me in the long term, and physics and mechanics also, two sciences for which I had great esteem, and wherein I was not unversed. My industry soon earned for me the reputation of an assiduous scholar, attentive to his studies and punctilious in the execution of his practical experiments. At the end of my third year, having excelled in the required courses, both speculative and practical, to the satisfaction of my tutors, I was raised to the degree of Master of the Academy.

Because I had proved myself a scholar of no little diligence and uncommon aptitude, it was the general opinion of both my professors and my fellow students that I would continue at the Academy and take my doctorate. As this would require me to add to the accomplishments of the Academy some original work of my own devising—whether this were of a speculative nature or a practical—I saw no reason why I could not bring down two birds with the same stone by combining my doctoral studies with my lifes ambition of replicating the Great Keeper of Time.

Believing myself to be in this regard a sort of pioneer, striking out into uncharted waters, I anticipated that my enterprise would be greeted with expressions at least of respect, if not of awe. But when I disclosed my plan to my colleagues, I was met, on the contrary, with a sort of a smile which usually arises from pity to the ignorant. Undaunted by this less than favorable reception, I at length shared my intentions with my professor, a man of great learning and not a little wisdom. He was of the firm opinion that such an ambitious project belonged properly to the Academy of Projectors in Lagado, the metropolis of Balnibarbi, which was situate on the mainland, and he advised me to look around for a more appropriate subject for my doctorate—which I understood to mean, a subject more fitting for a member of the Academy of Natural Philosophy. I persisted, however, in my initial design, and laid out the practical benefits that I believed would result from such an accomplishment. I insisted, furthermore, on my staying in Laputa, arguing that I could not hope to succeed in my endeavors without that I might have regular access to the Great Keeper of Time.

My professor listened to me with patience and did not speak again until I had exhausted every argument I could muster to my defence. When, finally, I fell silent, he sighed and invited me to sit down. I saw plainly that he intended to disclose something of great import to me:

— When Chronos, he began, first constructed the Great Keeper, many of his colleagues, envious of his success, attempted to replicate his achievement, believing that in this way they could steal for themselves some of the renown which the invention had won for him. They failed, every last one of them.

As I listened to my professor, I dimly recalled how our guide had told my father and myself something of the same import more than a dozen years previously. At some point in the course of those years, this memory must have slipped from my mind.

— The best of their devices, my professor continued, could not keep time with the Great Keeper for even one hour. Far from diminishing the fame of Chronos, they had merely transformed him into a legend, and destroyed their own reputations to boot. More than a century has passed since a member of the Academy last attempted to do what Chronos did. That is why your colleagues smiled when you told them of your ambitions. The Great Keeper of Time is a graveyard of failed careers. It is as vain to spin straw into fine gold as it is to replicate this device.

I left, downcast in countenance and dejected in spirit, with all of my plans in shreds. But I had invested so much of my life in the accomplishment of this one thing that I was loth to abandon all hope while there yet remained a single stone unturned.

There was a great lord at court, nearly related to the king, and for that reason alone used with respect. I approached this illustrious person and entreated him to intercede in my behalf with his majesty, which he accordingly did, as he was pleased to tell me, with expressions of the highest acknowledgment. Some days later, to my great surprise, a messenger called on me at my apartment and served me with a royal summons to attend on his majesty the following morning.

The next day I put on my finest apparel and repaired to the palace at the appointed time. I was let into the chamber of presence, but his majesty took not the least notice of me by the concourse of all the persons of distinction belonging to the court. At length, however, I was called forward by the royal attendant. The great lord who had interceded in my behalf being present, he explained to the king the nature of my petition and how it was my ambition to invent a practical keeper of time in imitation of the Great Keeper.

His majesty discovered not the least curiosity to inquire into the natural laws that governed such a device as I hoped to construct, but confined his questions to the military and economic purposes to which my chronometer might with advantage be put. The halting responses I gave to these inquiries he received with great contempt and indifference. But, not to trouble the reader with a particular account of my distress, let it suffice that his majesty, blessed with some tincture of common sense, concluded that one chronometer was insufficient for a kingdom as large and as prosperous as Balnibarbi was and that the replication of the Great Keeper was a worthy cause for a member of the Academy to pursue. At the prompting of my lordly intercessor, he issued a royal proclamation with the purport that I should be granted all that I required to the accomplishment of this end—wherein it were much to be desired that the Monarchs of Europe would imitate him.

I did not tarry to trade on his majestys good name. Armed with his proclamation, I set out like a military strategist embarking on a lengthy campaign. Within a sennight I had procured for myself a workshop adjacent to the Hall of Sciences, which I fitted out with all the furniture and appurtenances appropriate to the art of clockmaking. I also retained the services of two apprentices to lighten the manual side of the labor, and without further delay we applied ourselves to the task in hand.

In my innocence, I had persuaded myself that this task would entail little more than the opening up of the Great Keeper, the close examination of its working parts, and the replication of those parts in miniature. But a little thought ought to have disabused my ignorance, for if the problem was so easy of solution, why had no one yet solved it? As I stood in front of the Great Keeper of Time and examined its exterior minutely, the answer became clear to me. In order that the world might do him justice as the sole inventor of this wonderful machine, Chronos had constructed it in such a manner that it could not be opened up but its inner machinery would be destroyed in the process. I, who had had the temerity to fancy myself royal clockmaker to his majesty the King of Balnibarbi, had nothing to guide my labor but the dial of the great chronometer and the movements of its three hands. The internal mechanism of my clock I would have to invent out of my own head, just as Chronos had devised his out of his head.

It would not be proper, for some reasons, to trouble the reader with the particulars of my struggle to devise an instrument that would tell the time with the precision and accuracy of the Great Keeper. Let it suffice to say that I was able in the compass of five years—although, I confess, with the utmost difficulty—to accomplish this task to my own satisfaction. After more than a dozen failures, I succeeded in constructing a clock of modest proportions, and which I had good reason to hope would, once synchronized and wound up, keep time with the Keeper. When I informed the Laputan authorities of my achievement, I was commanded to submit my device to the review of my peers before his majesty would acknowledge it or condescend to view it.

It was with great trepidation that I took my chronometer to the Hall early the next morning and displayed it to a select handful of my colleagues. They were initially skeptical, as becomes all scholars of natural philosophy, and declared themselves unimpressed by the device. When placed next to the Great Keeper of Time, my diminutive clock, I own, lacked presence. Nevertheless, they were satisfied that it gave every appearance of telling the time and that it could not be easily dismissed without a proper trial. A day, therefore, was appointed for a public demonstration before his majesty the King, the Academy of Natural Philosophers, the Elders of the City, and all the populace of Laputa.

On the appointed day, curious onlookers arrived from all parts of the island and thronged the Hall to see what it was that merited so uncommon a reception. They beheld me and my chronometer with all the marks and circumstances of wonder. Their numbers were soon swelled by the whole Conclave of Natural Philosophers and Senate of the Elders of the People. At length, when all these persons of prime quality were convened, his majesty was announced and his subjects rose to their feet as a mark of respect due to royalty. The king entered, with all his court in train, and took his seat in the place of honor.

He cast his eyes over my device—somewhat disparagingly, I thought. Then he turned to me and addressed me in a rather brusque manner:

— Well, Clockmaker, we havent all day. Let us see what your infernal machine is capable of.

An ominous silence fell upon the great Hall, broken only by the tick-tock of the Great Keeper of Time. With the help of my apprentices, I wound up my clock, synchronized it with the Keeper, and set it in motion. The silence was now broken by the monotonous tick-tock of the two clocks. For several minutes all eyes followed the movements of the two second hands to mark whether they should fall out of step with each other. All ears, at the same time, were strained to detect the slightest delay between the ticks of the two clocks. But even after the lapse of what must have been more than one half hour, both clocks remained perfectly synchronized to the second.

His majesty, growing weary of the dull spectacle, conferred briefly with his prime minister. A moment later, without taking any further notice of me or my clock, he rose and marched briskly out of the Hall, followed by his entire train. One by one the remaining spectators also lost interest and drifted away, natural philosophers, Elders and commoners alike, leaving only myself, my two apprentices, and a handful of natural philosophers—to wit, the Grandmaster of the Academy, whose duty it was to deliver the final verdict on my clock, and those of his colleagues that were most interested in the science of timekeeping.

Even we began to tire of our vigil as darkness fell over Laputa. The two clocks were still perfectly synchronized. Finally, some hours after midnight, the Grandmaster declared my chronometer a success and dispatched messengers to apprise the king and the Elders of the City of his verdict. In due course his majesty, by the advice of several worthy persons, issued a royal decree with effect that copies of my device be constructed under my supervision and distributed throughout the realm. My chronometer, the form and contrivance of which I was commanded to delineate on paper, became, in process of time, an household item, as common in the homes of Balnibarbi as a water closet or a garden rake. In less than one year, specimens of my clock small enough to sit in the pocket of a mans waistcoat were being bought and sold across the kingdom for little more than one or two guineas.

I was handsomely rewarded for my efforts. Wealth and honors alike were heaped upon me and I returned to Lindalino a rich and famous man. A father was never so proud of his son as my father was the day that the good people of Lindalino paraded me through the streets and bestowed upon me the freedom of the city of my birth. The custody of my chronometer I had left in the hands of the Academy, with minute instructions touching the proper maintenance of its mechanism and liberty to dispose of it as they or the king should think fit. After five years of ceaseless toil, and with a royal pension to support me, I flattered myself that I had earned an early retirement.

One year later, as the anniversary of my great triumph approached, I received a letter from the Grandmaster of the Academy requesting that I return forthwith to the Hall of Sciences to discuss a matter of some importance. Surmising that my expertise as a clockmaker, which was now firmly established throughout the realm, was required for some delicate purpose, I set off in the highest expectation of increasing both my reputation and my wealth.

When I arrived in Laputa the Grandmaster met me in person and conducted me on foot to the great Hall of Sciences. Along the way I asked him the nature of my visit, but he refused to divulge any information on the matter, indicating by his silence that he adjudged it preferable to let me discover it for myself when we should reach the Hall.

With the exception of two other members of the Academy, who were evidently expecting us, the place was deserted. I subsequently discovered that the Grandmaster had closed the Hall of Sciences to the public on some trivial pretext or other. His two colleagues were standing on either side of something I had not laid eyes on for the best part of a year: my chronometer. My heart skipped a beat as the horrible thought flashed across my mind that my clock had stopped running, but I then observed that the second hand was faithfully telling off the seconds as was its wont.

— I hope there is no problem with my chronometer, I inquired timidly, examining the device up and down and convincing myself that everything was in proper working order.

The Grandmaster, who had not uttered a single word since I had set foot on Laputan soil, continued silent. He merely indicated with a glance the Great Keeper of Time. I had been so engrossed with my own creation that I had forgotten all about Laputas monumental chronometer, the wonder of the world that had all but bereft me of my senses the day I had first laid eyes on it. Now, for the first time since entering the Hall, I looked at it. I heard its imposing tick-tock. I watched its second hand tell off the seconds as faithfully as my own clock did. I even waited to make sure that its enormous minute hand was still faithfully telling off the minutes. It was.

I turned back to the Grandmaster and expressed my continuing incomprehension with a gesture:

— I dont understand, I said. What am I supposed to see?

Finally, the Grandmaster spoke:

— Look at the two clocks!

I looked. At first I saw nothing amiss. Both clocks gave every appearance of working as they should. But then I looked more closely and with greater minuteness, and I saw what had occasioned my return to Laputa: my clock was one second slower than the Great Keeper of Time.

I realized at once what had happened. Or, rather, I realized at once what was happening, what had been happening from the day I wound up my clock and synchronized it with the Keeper, and what would continue to happen indefinitely into the future. My clocks mechanism was infinitesimally slow compared to that of the Keepers, and it always had been. The difference from second to second, or from minute to minute, or from hour to hour, was too small to be detected by the human eye. Even after the passage of several days—or months, for that matter—the discrepancy continued to elude even the keenest observation. But after the lapse of one year, the tiny diurnal discrepancies had accumulated to one whole second, which anyone but a blind man could discover for himself.

I explained all of this at some length to the Grandmaster and his colleagues, adding, by way of exonerating myself:

— You must remember that when I set about my task of replicating the mechanism of the Keeper, I was not permitted to examine the inner workings of the great chronometer. I was obliged to restrict my observations to the Keepers face. I had nothing to guide my work but appearances. In constructing my clock, I was merely trying to save those appearances. It would be an extraordinary—nay, a miraculous—achievement if I had replicated precisely the actual workings of the Keeper without ever having laid eyes on them. Instead, I came up with a mechanism of my own, one that did a very good job of replicating the movements of the three hands on the Keepers dial. A very good job, but not a perfect job.

The Grandmaster was not impressed with my explanation, but he was too intelligent and well-educated a man not to see that what I spoke was the truth—the whole truth—of the matter:

— But can you fix it? he asked.

— Its not broken, I replied.

— The problem, then, if not your wretched clock! Can you fix the problem?

I considered the matter in silence for several minutes:

— Given time, I finally replied (not intending any facetiousness by this remark, which slipped out accidentally), I suppose I could construct a new clock from the ground up. Or it might be possible to modify the present mechanism so that it will run just a little faster. One second per year faster, to be precise. But you must understand that a new clock is just as likely to differ in its internal mechanism from the Keeper. It may keep perfect time with the Keeper for one year, or for two years, or for ten years. But it will only be a matter of time before I or my successor is back here in this Hall trying to explain why his clock is one second slow or one second fast.

The Grandmaster walked up and down the Hall, and pondered the predicament in which I had placed him. His two colleagues, who had followed our conversation in silence, watched him patiently. At length, having reached some resolution, he returned to where we were standing:

— What should we do in the meantime? he asked. Hope that no one notices this discrepancy? Or quietly adjust your chronometer and say no more about it? If we choose the latter course, we must needs repeat the deceit on a yearly basis. Perhaps we should institute a new custom analogous to the quadrennial addition of a leap day to the calendar?

— I dont think that would be a wise course of action, I said. Remember that there are now countless copies of my chronometer scattered throughout the realm and even—if I might be forgiven an expression of personal pride—throughout the world. And every one of them was built to the same specifications as this one. It is only a matter of time before the public becomes aware of the imperfection of my model.

The Grandmaster, a scholar so distinguished for his veracity that he could not tolerate the slightest imposture, sighed and nodded his head. We could tell that he was resigned:

— I shall announce our discovery to the king as soon as possible. Let us hope his majesty receives this news as dispassionately as you have received it.

The Grandmaster need not have been anxious. When his majesty learnt how far short my clock fell of absolute perfection, he is reported to have guffawed, before delivering the following sagacious remark:

— One second! Why, only a natural philosopher could bewail the loss of a single second in a year. Would that the royal treasury was as imperfect.

And on this point the king proved to be in complete harmony with the majority of his subjects, who agreed that the loss of one second in a year was rather a cause for celebration than for concern. Only my colleagues at the Academy, it seems, were at all perturbed by the failure of my chronometer to remain in perfect synchronism with the Great Keeper of Time. To some it was a disappointment to be borne with patience and equanimity, but to others it was a challenge. Those natural philosophers who were unable to improve upon the work of Chronos—or unwilling to risk the loss of their reputations should they be so foolhardy as to make the attempt—were only too happy to try their hands at improving upon my imperfect work.

Within the year, there was hardly a workshop on Laputa that was not the scene of a fresh experiment in the art of clockmaking. And in Lagado, the Academy of Projectors was, for the greater part of the ensuing decade, wholly given over to this newly popular craft. Throughout the Kingdom of Balnibarbi, there was hardly a natural philosopher who did not turn his attention to this problem, let his interest be of the practical or of the speculative sort. But their success has not hitherto been answerable to their ambitions. At the time of this writing, my chronometer is still the best model we have of the Great Keeper.

The reader will not be surprised to hear that I too was encouraged to enter the lists—to break a lance, as it were, against myself. And for a brief spell, I own, I was tempted to take up this challenge and prove my genius a second time. I had a conjecture of my own for the amelioration of my clock, which, however, I shall not obtrude upon the reader. This improvement offered the prospect of reducing the inaccuracy of the device to one second in two years. But I forbore troubling myself any further with the art of clockmaking. I thought it more consistent with prudence and justice to pass the remainder of my days with my wife and family.

My younger colleagues at the Academy have no such forbearance. They envisage an endless series of clocks stretching into eternity, each one more accurate than its predecessor, but all falling short of the absolute perfection of the Great Keeper of Time.

But I have now done with all such visionary schemes for ever.

THE END

References

- Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, The Prose Works of Jonathan Swift, D. D., Volume VIII, Edited by G Ravenscroft Dennis, George Bell & Sons, London (1905)

Image Credits

- Clock Tower: WallpaperUP, © 2017 Calimero, Unknown License, Fair Use

- Laputa and the Kingdom of Balnibarbi: Map of Laputa and Balnibarbi for the 1726 edition of Jonathan Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver’s Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, Public Domain

All hope is not lost at last!

Congratulations on your acheivements....

Every man is permitted to fail. Like a gold before it would be refind it must pass through the fire ,this is how failure is, when you fail its part of your daily living because if you don't fail before you achieve your dreams you will not value that achievements....

Great men and women fail but they don't give up. If you don't fail, you will not have a story to tell when you stand.

Tnx for sharing your experience, it was really nice and worth reading.

And thank you for the comment!

You are welcome sir

Happy steeming

Nice fantastic post Happy 2018 Contribution comment#

Thanks, and a Happy New Year.

very good post u always share nice post keep it up

Thank you.

fascinating story. keep posting stuff like that. stay blessed <3

Thanks, and you too stay blessed.

My pleasure <3

Excellent story writing. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you. Happy New Year.

Hello Fantastic post friend greetings

Hello, and thank you.

Very good story writer you are dude.

How are you dear. I hope your alright dear

Approach your publication by a Resteemeado and I think it is very interesting what you write. Success

A story that tells the story of Cronos, great publication always loved reading stories

its a great achivement...thank you..@harlotscurse

@upvote done